This blog was produced for the RCPCH Safety eBulletin. Please note Patient Safety Spotlights are all personal practice blogs and any information shared are not endorsed RCPCH guidance – readers should use their clinical judgement.

The life-saving benefits of antibiotics in children are well understood, with the intravenous (IV) route often chosen as default for serious infections requiring hospital admission. However, many intravenous antimicrobials are broad spectrum. With the mounting evidence of the individual and population risk of harm from broad-spectrum antibiotics (1), alongside the reassuring safety profile of many enteral regimens (2), clinicians are encouraged to take an informed and balanced approach in the safe treatment of childhood infections.

This blog explores:

- Use of intravenous antibiotics in the UK

- Risks of harm linked to broad-spectrum antibiotics and what we suggest clinicians can to do mitigate this

- Risks of harm linked to intravenous antibiotics, and where literature suggest it is safe to use the oral route instead

- Evidence for safe early IV to oral switch and exclusive oral regimens in children

- Resources and clinical decision support in paediatric infection management

- A collaborative approach across hospital networks to support optimal antibiotic use in children

About the authors

Dr Charlotte Fuller is a Clinical Fellow in Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology at Leeds Children’s Hospital and Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Scholar at the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC).

Dr Sanjay Patel is a paediatric infectious diseases and immunology consultant working at Southampton Children’s Hospital and is the national clinical advisor for paediatric antimicrobial stewardship at NHS England.

Together, they co-lead an NHS England–funded paediatric antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) network project being piloted in four regions of England. The project supports a collaborative approach to embedding stewardship across secondary care paediatrics. This model has been strengthened by the development of a paediatric AMS education programme, supported by BSAC.

When are intravenous antibiotics used in the UK?

Children presenting to UK hospitals with suspected bacterial infection are often commenced on IV antibiotics, with third generation cephalosporins (such as ceftriaxone) commonly used in paediatrics. They feature as the first line antibiotic in empirical guidance for sepsis because they are broad-spectrum and have excellent central nervous system penetration, meaning they are effective against many groups of bacteria when the pathogen and focus of infection is unknown.

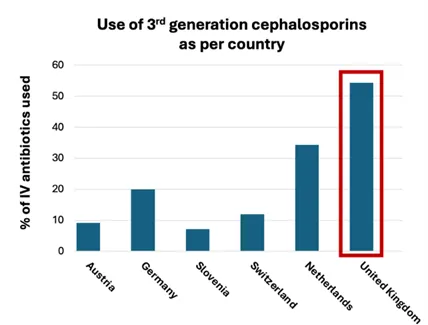

The UK uses more third generation cephalosporins than other European countries, where narrow-spectrum antibiotics targeted to the likely source of infection are more prevalent (3). Narrow-spectrum antibiotics target fewer groups of bacteria but can be just as effective in those they do work against.

What are the risks of harm associated with broad-spectrum antibiotics to children and neonates?

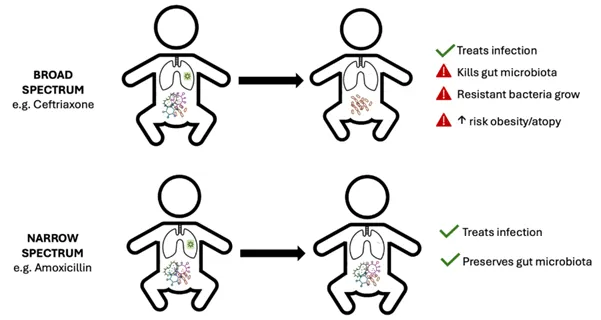

Although broad-spectrum agents often work against the problem pathogen, they are also effective against gut flora and other commensals which are established in, and contribute to, health. Disturbance of gut flora is often the mechanism behind the gastrointestinal (GI) side effects reported, and as the microbiota recovers, resistant bacteria are likely to emerge and/or overgrow.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) affects both the individual (reducing effective response to antibiotics in future infections) and the wider ecosystem (resistant bugs shared with others and the environment). Modern medicine relies upon antibiotics to enable key treatments, such as surgery and anticancer chemotherapy, as well as the treatment of simple infections. The speed at which resistance to antimicrobials is growing worldwide raises much concern, with the WHO listing AMR within the top ten global public health threats to humanity.

In addition, there is growing evidence demonstrating the link between early exposure to antibiotics in infancy and long-term conditions such as asthma (4) and obesity (5) in later childhood.

Narrowing the spectrum of antibiotic exposure where safe to do can still treat the infection whilst reducing the risk of antimicrobial resistance and other effects on long-term health (see infographic below).

What can paediatricians do to reduce unnecessary broad-spectrum exposure?

The exposure of broad-spectrum antibiotics to UK children predominately occurs in hospital when sepsis is suspected. Children with sepsis can rapidly deteriorate, demanding senior clinical input in suspected cases. However, the likelihood of sepsis in febrile children is lower than that of adults, with under 4% of infants screened for sepsis in UK emergency departments having positive blood or CSF cultures (6). Much of the fever burden in young children comes from viral infections in developing immune systems, and the introduction of highly effective conjugate vaccines over the last 20 years has significantly reduced the incidence of community-acquired sepsis in young children.

The NICE-recommended sepsis screening tool supports staff to think of sepsis and is designed to prompt a senior review to consider the likelihood of a significant bacterial infection. Triggering the tool does not mandate starting IV antibiotics, rather to advocate for senior decision-makers to consider sepsis as a diagnosis and act accordingly.

Clinicians often do have time to consider the case in front of them. In their most recent sepsis statement, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges refers to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidance that recommends administration of antibiotics within one hour to those with septic shock, and within three hours in sepsis-associated organ dysfunction without shock to allow for appropriate care (7,8). Those with potential sepsis without shock require thorough clinical assessment, appropriate investigations to decide the likelihood of a serious bacterial infection and the site of infection as well as close clinical monitoring.

By adopting this permissive 3-hour approach in children presenting with sepsis without shock, front-line clinicians are more likely to be able to identify the location of the infection appropriate narrow-spectrum antibiotics in line with regional or national guidance. Early identification of the source may also allow effective oral antibiotic therapy, which are often narrow-spectrum (eg penicillin based).

What are the risks of harm of intravenous antimicrobials?

- Drug adverse effects: The safety profile of first-line oral regimens used in children often surpass that of intravenous choices. IV gentamicin, a first line in suspected neonatal sepsis, provides an example of life-changing adverse effects on hearing and renal function. The adoption of early switch to penicillin-based oral antibiotics in babies with suspected early onset neonatal sepsis at the Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (9) has reduced the exposure of gentamicin from 3 to 1.7 doses per baby, and supported early discharge home, with no adverse effects on outcomes reported.

- Venous catheter risks: IV access presents an obvious risk of local infection, extravasation and thrombophlebitis. Daily cannula checks by nursing staff can help to mitigate this. Cannulation is traumatic for many children, and to both the parents and healthcare staff expected to restrain them. Running out of veins can necessitate need for more invasive central access.

- Time: A dose of IV antibiotic is estimated to take 40 minutes of nursing time to prepare and administer in children, pulling staff away from other duties at a time of deepening NHS workforce crisis.

- Families: In the absence of a robust hospital at home or outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) service, keeping a child in hospital for antibiotic administration places economic burden on families as they battle the loss of earnings, alongside childcare and transport costs and stresses.

- Sustainability impact: The environmental impact of IV therapy is driven largely by increased rate of admission and extending time in hospital, with additional impact from IV medications themselves, and single use plastic tubing, syringes and extension sets incinerated as clinical waste. Further information on sustainable paediatric practice can be found on the RCPCH Greener paediatrics pages.

Consider oral antibiotics

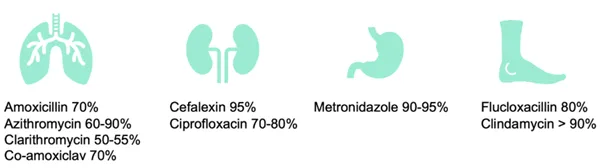

Many clinicians equate the hospitalisation of a febrile child with a bacterial infection with the need for IV antibiotics. Yet, the bioavailability for many first-line oral antibiotics is high enough to be effective. For example, 95% of the oral dose of cefalexin reaches the blood.

Providing that the drug concentration at the site of infection reaches effective levels, the route of administration is less important. From the bacterium’s perspective, the route the antibiotic takes is irrelevant.

Bioavailability information can be found at Electronic medicines compendium.

When are IV antibiotics required?

Although the default for administration is increasingly becoming the enteral route, clinicians are encouraged to consider the need for IV antibiotics, with the absolute indications being:

- Severe sepsis – where the time to reach therapeutic levels in the blood is vital, and where gut perfusion may be compromised

- Poor absorption from the GI tract or if patient refusal to take orally

- A lack of oral option due to resistance

In higher risk groups, such as confirmed bacterial infections in neonates, severely immunocompromised children or deep-seated infections requiring high tissue concentration, shared decision making with microbiology or infectious disease colleagues can help decide when to switch from IV to oral antibiotics.

What is the evidence for early oral switch from IV and exclusive use of oral antibiotics?

Several organisations have reviewed the evidence. In adults, the long-held belief that IV is superior to oral antibiotics to treat infections has been tempered by several large randomised controlled trials, including bacteraemia (10,11), bone and joint infections (12), and even infective endocarditis (13). In paediatrics, high-quality evidence now exists for early oral switch and even exclusive oral regimens in many infections previously considered to require the entire course to be given intravenously.

A 2016 systematic review (2) permitted a paradigm shift in practice for paediatricians managing childhood infections requiring hospitalisation, with a commentary by ADC Archivist (14). This table highlights this and other recent publications comparing IV vs oral antibiotics.

Selected recent antibiotic publications in children

| Condition | Historic Practice | Suggested practice | Reference |

| Community acquired pneumonia | Proportion of course IV route | Exclusively oral course for uncomplicated pneumonia; 1-2 days of IV for empyema prior to an oral switch | McMullan et al. (2016) Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: Systematic review and guidelines. The Lancet Infectious Diseases (2) |

| Upper urinary tract infection (UTI) in under 3 months | 7-10 days of IV antibiotics | Switch to oral after 3 days | Hikmat S et al. (2022). Short intravenous antibiotic courses for urinary infections in young infants: A systematic review. Pediatrics. (15) |

| Bone and joint infections | 6 weeks of IV antibiotics | 2-4 days IV for septic arthritis; 3-4 days of IV for simple acute osteomyelitis followed by PO switch. More recent RCT data has suggested oral only regimens for uncomplicated bone and joint infections | McMullan et al. (2016) Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: Systematic review and guidelines. The Lancet Infectious Diseases (2) Nielsen AB et al. Oral versus intravenous empirical antibiotics in children and adolescents with uncomplicated bone and joint infections: a nationwide, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial in Denmark. Lancet Child Adolesc Health (16) |

| Neonatal early onset sepsis | IV route for the duration of the course | PO switch at 48-72 hours | Carlsen et al. (2023) Switch from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics in neonatal probable and proven early-onset infection: a prospective population-based real-life multicentre cohort study. Archives of Disease in Childhood (17). |

What tools are available to support use of narrow-spectrum and oral antibiotics in children?

There are tools available to support prescribers to choose the right antibiotic, via the right route, for the right patient at the right time. The UK Paediatric Antimicrobial Stewardship Network (UK-PAS) empirical prescribing guidance (18) and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) common infection pathways (19) can support prescribers to decide on the choice of empirical antibiotic, including whether to start with an intravenous or an oral route. These recommendations are developed from the consensus of national UK experts in response to annual reviews of the evidence base, including incorporating evidence from NICE guidance.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) IV to oral switch decision aid is accessible online and provides a quick bedside tool to support the 48-72 hour review for patients initiated on empirical IV antibiotics (20). There is advice on from the Medicines for Children KidzMed resource for helping children to swallow tablets, as referenced in the February RCPCH Safety eBulletin.

What initiatives are being piloted to support clinicians in antibiotic use locally?

Over half of children in UK hospitals receive antibiotics, yet there exists little to no formal funding for in-patient paediatric antimicrobial stewardship services (21). Workforce challenges in AMS teams result in discrepancy between AMS services provided to adult and paediatric services (22), demanding a multi-disciplinary approach from clinicians, pharmacists, microbiologists and nurses. Inter-hospital collaboration via a regional paediatric AMS network has been successful in South Yorkshire (21), with improved prescriber confidence, better adherence to guidelines, and the proportion of patients receiving IV antibiotics past the point at which they meet criteria for oral switch halved across the region. This network model is currently being piloted in three other regions in England funded by NHSE, alongside a BSAC education programme designed to equip and empower local infection teams in district general hospitals to lead paediatric AMS interventions locally.

You can find out more about the regional paediatric AMS network model by contacting charlotte.fuller6@nhs.net.

Conclusion

The associated harms and wider effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics can be mitigated, in the absence of septic shock, by taking the time to identify the location of the infection to enable the prescribing of narrower-spectrum empirical therapy on initial presentation. Oral formulations can be utilised for simple infections where gut absorption is intact. Paediatricians can further reduce the IV burden with decision support tools to confidently consider early de-escalation from IV to oral therapy, with the backing of evidence for de-escalation in more complex infections. These strategies and resources are offered with an understanding of the challenges and nuances of managing children with infection.

References

- GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990-2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet. 404(10459):1199-1226.

- McMullan B et al. (2016) Antibiotic duration and timing of the switch from intravenous to oral route for bacterial infections in children: systematic review and guidelines. Lancet Infect Dis. 16(8):e139-52.

- Kolberg L et al. (2024). Raising AWaRe-ness of Antimicrobial Stewardship Challenges in Pediatric Emergency Care: Results from the PERFORM Study Assessing Consistency and Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescribing Across Europe. Clinical infectious diseases, 78(3), 526–534.

- Beier MA et al. (2025) Early Childhood Antibiotics and Chronic Pediatric Conditions: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Infect Dis. 232(3):659-668.

- Rasmussen SH et al. (2018) Antibiotic exposure in early life and childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 20(6):1508-1514.

- Umana E et al. (2024) Paediatric Emergency Research in the UK and Ireland (PERUKI). Performance of clinical decision aids (CDA) for the care of young febrile infants: a multicentre prospective cohort study conducted in the UK and Ireland. EClinicalMedicine;78:102961.

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (2022) Statement on the initial antimicrobial treatment of sepsis. Available at https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Statement_on_the_initial_antimicrobial_treatment_of_sepsis_V2_1022.pdf [Accessed: 04.02.26].

- Weiss SL et al. (2020) Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines for the Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis-Associated Organ Dysfunction in Children. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 21(2):p e52-e106.

- Health Innovation South West (2025) NOAH (Neonatal Oral Antibiotics at Home) Available at: https://healthinnovationsouthwest.com/programmes/noah-neonatal-oral-antibiotics-at-home/ [Accessed: 02.02.26].

- SNAP Early Oral Switch Domain-Specific Working Group and SNAP Global Trial Steering Committee; SNAP Trial Group (2024) Early Oral Antibiotic Switch in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteraemia: The Staphylococcus aureus Network Adaptive Platform (SNAP) Trial Early Oral Switch Protocol. Clin Infect Dis. 79(4):871-887.

- BALANCE Investigators, for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada Clinical Research Network, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Network (2025) Antibiotic Treatment for 7 versus 14 Days in Patients with Bloodstream Infections. N Engl J Med; 392(11):1065-1078.

- OVIVA Trial Collaborators (2019) Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotics for Bone and Joint Infection. N Engl J Med. 380(5):425-436.

- Iversen K et al. Partial Oral versus Intravenous Antibiotic Treatment of Endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):415-424.

- ADC Archivist. (2016) When to switch to oral antibiotics? Archives of Disease in Childhood 2016;101:1003.

- Hikmat S et al. (2022) Short Intravenous Antibiotic Courses for Urinary Infections in Young Infants: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics;149(2):e2021052466.

- Nielsen AB et al. Oral versus intravenous empirical antibiotics in children and adolescents with uncomplicated bone and joint infections: a nationwide, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial in Denmark. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2024 Sep;8(9):625-635.

- Carlsen EML et al. (2023) Switch from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics in neonatal probable and proven early-onset infection: a prospective population-based real-life multicentre cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 109(1):34-40.

- UK Paediatric Antimicrobial Stewardship Network. (2025) Antimicrobial Paediatric Guide UK-PAS. Available at: https://uk-pas.co.uk/Antimicrobial-Paediatric-Summary-UKPAS.pdf [Accessed 11.02.25].

- British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. (2022) Common infection pathways. Available at: https://bsac.org.uk/paediatricpathways/ [Accessed 11.02.25].

- UK Health Security Agency. (2024) Antimicrobial IVOS decision aid for paediatrics Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-intravenous-to-oral-switch-criteria-for-early-switch/antimicrobial-ivos-decision-aid-for-paediatrics-text-alternative [Accessed 11.02.25].

- Vergnano S et al. (2020) Paediatric antimicrobial stewardship programmes in the UK's regional children's hospitals. J Hosp Infect;105(4):736-740.

- Fuller C et al. (2024) P36 Improving AMS programmes for paediatric services via a shared post working collaboratively across five hospital trusts within South Yorkshire, JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, Volume 6, Issue Supplement_2, dlae136.040.