Clinical guidelines are sets of recommendations based on systematic research methods. Producing these requires advanced research skills and project management.

Below is a flowchart showing the stages of high-quality guideline development to meet the requirements for RCPCH endorsement.

Click on the headings in the flowchart to jump to the relevant section for information and resources.

All documents are available in the Downloadable resources for: box below each section.

Downloads may open in a new browser tab instead of downloading to your computer or device depending on your browser settings. If you cannot download the file, please email us at guidelines@rcpch.ac.uk.

Initial steps

Step 1. Register your intent to develop a guideline

- Complete our registration form and send to guidelines@rcpch.ac.uk. This information will also be helpful for the guideline scope.

Step 2. Agree support from RCPCH and sign the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)

- We may suggest a meeting to discuss your topic and send you an MoU to be signed by the developing organisation/group and RCPCH. The MoU sets out the expectations and responsibilities from both parties.

Step 3. Review the guideline development checklist for oversight of steps needed to deliver high quality guideline

- Downloadable resources for: Initial steps

-

Registration form (MS Word)

Guideline development checklist (MS Word)

Recruitment

Step 4. Recruit a Chair and key members for the guideline development group (GDG)

- RCPCH can support this process by providing the Chair and GDG responsibilities document with suggested responsibilities. The GDG will be finalised after the final scope is agreed.

Step 5. Ensure all members of the GDG declare their interests

- The Chair(s) and members of the GDG will need to declare their interests at the start of the process using the Declaration of interest form. Any changes to circumstances need to be communicated to the Chair(s) either verbally at meetings or by updating the forms. Declarations of interests must be recorded for all participants throughout guideline development and detailed in the guideline.

Step 6. Identify stakeholders for the guideline

- Stakeholders are organisations that the GDG identifies as having an interest in the clinical guideline topic or who represent people whose practice or care may be affected by the guideline. Patient organisations and pharmaceutical companies (where appropriate) and groups such as the RCPCH & Us Voice Network for children, young people, parents, carers and their families should be invited to be stakeholders for the guideline.

- During clinical guideline development, registered stakeholders should be invited to consult on the scope and guideline draft.

- Use our Stakeholder invitations template.

- If you would like RCPCH to send the draft scope and guideline to stakeholders, provide us with a stakeholders form detailing email addresses.

For more information on this stage, see 'Section 3.4 Who is involved?' in the RCPCH guideline process manual (page 12 in the download).

- Downloadable resources for: Recruitment

-

Chair and GDG responsibilities (MS Word)

GDG invitations template (MS Word)

Declaration of interest form (MS Word)

Stakeholder invitations template (MS Word)

Stakeholders form (MS Word)

Scoping

Step 7. Develop the draft scope

- Our scope template supports this.

- The scope sets out what the guideline intends to achieve. It identifies the remit, background, aims and objectives, clinical need for the guideline, target population, target audience and healthcare settings, timeline, clinical questions to be addressed and stakeholder representation.

- The clinical questions may include effectiveness of an intervention, prognosis, clinical prediction models for diagnosis or prognosis, experiences and views of patients, families, and service providers. They must be focused and specify the key issues and target population concerned.

- Questions about interventions should be framed in PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) format, (see example below) since these will form the basis of the evidence search strategy.

- An Example of PICO framed questions: In children and young people aged under 5 years with urinary tract infection (UTI) (population), does treatment with antibiotics for 10 days (intervention) compared with treatment with antibiotics for 3 days (comparator) reduce recurrence of UTI (outcome)?

Step 8. Consult on the draft scope, and finalise the scope

- It is critical that the draft scope is sent to stakeholders to allow objective assessment of the proposed content and applicability of the guideline. We suggest a consultation period of 4-6 weeks. The dates of consultation and list of stakeholders to whom the scope is sent should be recorded.

- Agree the final scope and finalise completion of the GDG.

- Update the scope based on consultation comments.

For more information on this stage, see 'Section 3.3 Scoping the guideline' and in the RCPCH guideline process manual (page 12).

- Downloadable resources for: Scoping

-

Scope template MS Word)

Consultation comments form (MS Word)

Consultation response table: record comments and responses (MS Excel)

Guideline development

Step 9. Develop a search strategy

- The development of an evidence-based clinical guideline requires a systematic literature review using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify the evidence.

- RCPCH has developed an eLearning module in undertaking systematic reviews (on RCPCH Learning).

- The search strategy will use the clinical questions set out in the scope, from which a PICO table may be developed.

- The search strategy should state the outcomes under consideration. These generally include mortality, quality of life and hospitalisation but could also include disease progression, medication side effects.

- Identify search terms including free text, keywords, phrases, and subject headings (where applicable).

- Define databases to be searched. Usually more than one database will need to be searched as a single database may only provide partial coverage of the medical literature for any specific topic. Specialist databases relevant to the topic should be considered. Suitable databases might include Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and The Cochrane Collaboration for Systematic Reviews.

- Set out the study types that will be accepted, eg:

- systematic reviews

- randomised controlled trials (RCT)

- non-randomised studies (NRS) if there is insufficient RCT evidence, provided that there is adjustment for key confounders (age, ethnicity, comorbidities, and baseline health).

Step 10. Collate and appraise the evidence

- Publications identified from the search should be screened for relevance by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria set out in the search strategy. This should be undertaken independently by two reviewers. Where reviewers disagree about whether a study should be included this can be resolved by discussion, or by using a third reviewer. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) is a widely used and clear method for detailing the search results and flow of information.

- Each relevant publication should be critically appraised using pre-specified criteria to assess the quality of the evidence with respect to its methodology and the significance of the results. We recommend using a critical appraisal checklist, such as the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (CASP) checklists.

- The resulting references are best stored in a spreadsheet or using bibliographic and reference management software such as EndNote, Mendeley, Reference Manager or RefWorks.

- Literature searches may need to be re-run to identify further evidence that has been published since the initial search was conducted. We suggest that a search should be rerun if more than 18-24 months have lapsed before conducting the search and publishing the guideline.

Step 11. Grade the quality of the evidence from the retrieved publications

- We recommend using GRADE (Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations) to assess the quality of the evidence. GRADE categories of evidence quality:

- [A] high – Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect

- [B] moderate – Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

- [C] low – Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate

- [D] very low – Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

- GRADE categorises evidence from RCT and observational (non-randomised studies) from high to very low (as shown above).

- RCT are considered to be of highest quality since successful randomisation eliminates confounding factors (known and unknown). In the GRADE system, evidence from RCT is initially considered to be high. There are then five criteria that can be used to downgrade by 1-3 categories. These are:

- Risk of bias in individual studies – due to limitations in study quality, such as inadequate blinding

- Inconsistency of results between studies

- Indirectness of evidence – eg participants were children although the systematic review was about adults

- Imprecision – due to wide confidence intervals, which may be a consequence of a small number of studies or if there were few events

- Publication bias – the publication or non-publication of research findings based on the nature and/or direction of their results.

- Evidence from observational studies is initially considered to be low; however, this can be upgraded if there is:

- a large effect where there is strong evidence of association based on consistent evidence from two or more non-randomised studies (eg a three-fold risk of head injuries in cyclists who do not wear helmets compared with those who do)

- a dose-response gradient (a larger dose of treatment leads to better outcomes)

- plausible confounding factor(s) not adjusted for in the original study, which would alter the outcome of the study.

-

Findings may be summarised in the evidence table template provided or, for example, GRADEpro.

Step 12. Consider options when evidence is absent or of poor quality (common in paediatric healthcare)

- Make recommendations based on consensus within the GDG (these recommendations will always be weak recommendations, which should be acknowledged in the guideline).

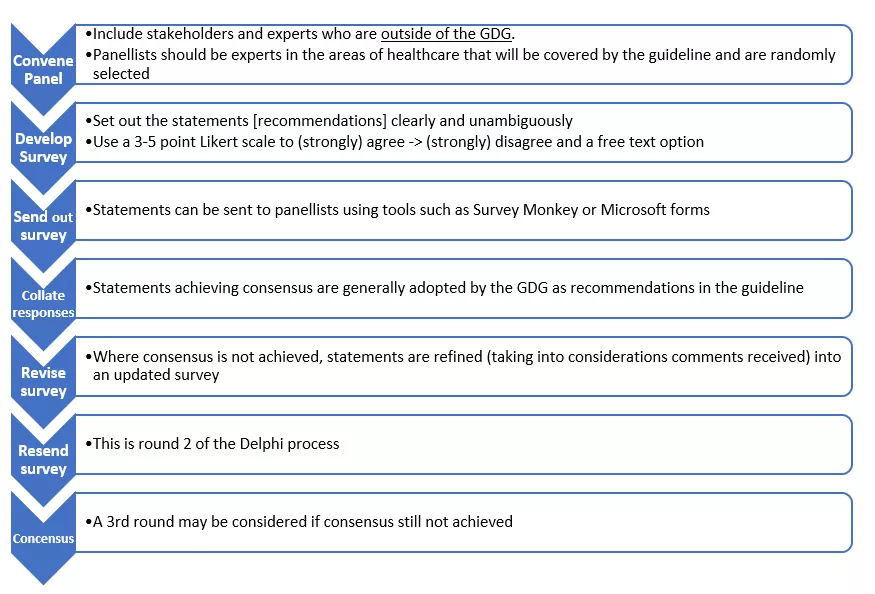

- Make recommendations using formal consensus techniques, such as Delphi - see the Delphi process summary flowchart figure below. Using this technique introduces rigour and objectivity, reduces risk of bias and allows an assessment of likely implementation of recommendations.

- The first step in the Delphi process involves identifying a panel of participants, including stakeholders who are outside the GDG. Panellists should be experts in the areas of healthcare that will be covered by the guideline and are randomly selected. We suggest that three panellists from each healthcare area and three parents / young persons are invited.

- Panel members are anonymised to prevent any individuals from unduly influencing the outcome.

- At the point of invitation, panellists should be asked whether they agree to participate, advised of the likely dates that they will receive the statements and advised that there will usually be 2-3 ‘rounds’ of statements requiring their responses.

- A set of statements (recommendations) is drafted and shared with panellists, who are invited (generally via email) to agree or disagree with these statements in a 3–5-point Likert scale (1 being strongly disagree, 5 strongly agree) to indicate the level of agreement / disagreement with any given statement. A free text box for comments and ‘outside area of expertise’ option should be provided.

- Statements must be clear and unambiguous and should not contain clauses or subpoints to minimise the risk of panellists agreeing to one part and disagreeing with other part of statement with loss of consensus.

- Statements are generally sent to panellists using tools such as Survey Monkey or Microsoft Forms.

- A predefined threshold for consensus must be determined at the start of the Delphi process (often defined as 75% of ratings falling in either the agree or disagree category).

- Statements achieving consensus are generally adopted by the GDG as recommendations in the guideline.

- Where consensus is not achieved, the statements are refined by the GDG and sent back to the panellists in the second round of the process. Statements may also be dropped as agreed by the GDG.

- Where no consensus is achieved after 3 rounds, it is unlikely that a recommendation can be made.

Figure 1: Delphi process summary flowchart

Step 13. Formulate the recommendations:

- The GDG will translate or ‘link’ evidence into recommendations.

- The links between the recommendations and the evidence (or consensus) that supports them should be explicitly set out in a rationale for each recommendation.

- The language used in recommendations should be concise and unambiguous, to facilitate seamless translation into practice.

- Where possible, recommendations should take into account the resource implications of implementation.

- The strength of any recommendation should be made clear.

- A strong recommendation is one that most service users would agree with. Strong recommendations generally derive from high quality evidence or formal consensus of experts who are independent of the GDG.

- A weak recommendation reflects poor quality or no evidence and lack of formal consensus.

- The strength of recommendations may be represented alpha-numerically (usually in brackets after the recommendation), where a strong recommendation is denoted by ‘1’, and a weak recommendation by ‘2’. This is combined with the letter that best describes the quality of the evidence, based on GRADE criteria as noted above, where A represents high quality evidence, B moderate, C low and D very low. In this respect, the strongest possible recommendation would be denoted by [1A], reflecting GDG consensus and high-quality evidence or formal consensus), whilst the weakest recommendation would be denoted by [2D], where evidence is absent or of low quality, where there is no formal consensus, but GDG members are in overall in favour of making the recommendation.

- The strength of a recommendation may also be highlighted through its wording; this is the approach used by NICE.

- For recommendations that reflect strong evidence, directive language (e.g., offer, do not offer, advise, ask about) should be used.

- For recommendations that reflect weak evidence or GDG consensus wording such as ‘consider’ is more pertinent.

- Where there is a legal duty to apply a recommendation or where the consequences of not following a recommendation are serious, words such as “must” or “must not” may be used with a clear reference to the legal framework.

- As a general principle, drug dosages should not be stated in recommendations if accessible in readily available formularies. For drug dosing strategies that are not easily accessible, e.g., for off-label or unlicensed medicines, these should be checked in the electronic Medicines Compendium, British National Formulary for Children and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guideline.

- If any off-label medicines or devices are recommended for use, there should be a standard disclaimer attached to the recommendation.

Step 14. Make research recommendations

-

In areas where evidence and consensus are lacking, it will not be possible to make recommendations for clinical care. GDG members should make research recommendations if they believe that these will impact on future decision making. NICE recommend making up to five research recommendations.

Step 15. Develop audit criteria for recommendations

-

Audit criteria help develop ‘SMART’ (specific, measurable, achievable, reproducible, timely) recommendations and may assist in implementation of the guideline.

Step 16. Identify potential barriers (and facilitators) to implementation

- Health professionals may doubt the validity of evidence upon which the clinical guideline is based or may be reluctant to alter their practice where there is no perceived necessity for change.

- Patient preferences may differ from guideline recommendations (note the critical role of lay representation on the GDG).

- Structures and systems may have to be changed or more resources allocated, such as higher numbers of staff, specialised staff, new equipment, or different drug treatments.

- Factors that may facilitate change include multi-professional collaboration, ownership, and enthusiasm from professionals (‘champions’) and a supportive. environment that is receptive to change.

Details to be included in the final guideline:

- Background information on the illness/condition

- Aims and scope of the guideline

- Names and affiliations of GDG members and Delphi panellists (if applicable)

- Declarations of conflict of interest of GDG

- Details of the clinical guideline methodology.

- Search strategies employed, databases searched, and the time period involve

- Criteria for including/excluding evidence (this may be covered in the scope)

- Description of process for grading of evidence

- Description of formal consensus methodology, if used.

- Recommendations, research recommendations and audit measures

- Identification of potential barriers to implementation

- A lay summary

For more information on this stage, see 'Section 3.6 Developing clinical questions', 'Section 3.7 Identifying the evidence', 'Section 3.8 Evaluating, synthesising and presenting the evidence', 'Section 3.10 Formulating recommendations' and 'Section 3.11 Writing the guideline' in the RCPCH guideline process manual (PDF, page 17).

- Downloadable resources for: Guideline development

-

GDG agenda template (MS Word)

Search strategy (MS Word)

Guideline template (MS Word)

Evidence table template (MS Word)

Write up

Step 17. Prepare the final draft guideline for consultation

- The final draft guideline should reflect the above steps and include the information detailed in the previous step. You can use our guideline template.

- A lay summary should be included in the draft guideline, setting out why the guideline was developed and the key changes to clinical practice that may be achieved following implementation.

- The guideline should be updated within five years. A review date should be added, after which the guideline, if not formally reviewed, would no longer be valid.

- Downloadable resource for: Final write up

-

Guideline template (MS Word)

Consultation and final write up

Step 18. Send the draft guideline for consultation to stakeholders

- The stakeholders should be the same as those to whom the draft scope was sent.

- We suggest setting a consultation period of 4-6 weeks.

- The dates of consultation and list of stakeholders should again be recorded.

- You can download our consultation comments form and consultation response table templates.

- Disseminating the key messages, as well as PowerPoint presentations, webinars, and podcasts.

- Update the draft guideline based on consultation comments.

Step 19. Set out a plan to update the guideline

- Clinical guidelines need to be up to date to be useful.

- We recommend reviewing clinical guidelines at least every three years, or sooner when new evidence emerges that is likely to influence the recommendations.

- We recommend updating guidelines every five years, or earlier if there are changes in evidence on existing benefits and harms of interventions, or availability of interventions.

- An expert review panel (consider 5 to 8 clinical experts in the relevant topic area) can be recruited to agree on the extent of the update.

- An evidence review, as set out above, should be undertaken and sent to key stakeholders to gather views on the need to update the guideline and any existing issues with the current recommendations.

For more information on this stage, see 'Section 3.12 Consultation and external review' in the RCPCH Guideline Process Manual (PDF, page 28).

- Resources - Consultation

-

Consultation comments form (MS Word)

Consultation response table: record comments and responses (MS Excel)

Publish and disseminate

Step 20. Prepare the guideline for publication

- Once the final guideline has been finalised, prepare it for publication. Inform stakeholders and relevant paediatric groups of the publication date to help with dissemination and provide them with the final copy.

Step 21. Publish the guideline

- Publish the final guideline and place it in your organisation/group webpage and promote the link via social media and email communications.

- RCPCH can help disseminate further by promoting it via social media and we will place it in our Clinical Guideline Directory. Ensure you distribute educational materials and promote these as well.

For more information see 'Section 3.13 Endorsement and accreditation' and 'Section 3.14 Presentation, Launching and Promoting the Guideline' in the RCPCH Guideline Process Manual (PDF, page 29).

Glossary

- AGREE II tool (The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) - a tool that assesses the methodological rigour and transparency in which a clinical guideline is developed.

- Clinical guidelines - Statements that include recommendations intended to optimise patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options1.

- Clinical guidance – documents that aim to address a clinically important topic (diagnostic, therapeutic, or laboratory based) of broad clinical interest for which high-quality evidence, typically from randomized trials, is lacking or is unlikely to be developed.

- Conflict of interest - An interest that might conflict, or be perceived to conflict, with a person's duties and responsibilities during guideline development.

- Consensus methods - Techniques that aim to reach an agreement on a particular issue. Formal consensus methods include Delphi and nominal group techniques, and consensus development conferences. When developing guidelines, consensus methods may be used when there is a lack of strong research evidence on a particular topic.

- Consensus statement - Recommendations developed based on a collective opinion or consensus of the convened expert panel.

- Consultation - The period during guidance development when stakeholders or interested members of the public can comment on draft scopes and guidance.

- CQIP Committee (Clinical Quality in Practice) – this committee supports the development, dissemination and promotion of clinical guidelines, national audits and quality improvement activity to support clinicians in improving the quality of clinical practice and patient care.

- Delphi method - A technique used for reaching agreement on a particular issue, without the people involved meeting or interacting directly. It involves sending those involved a series of statements and seeking their views. After completing each round, they are asked to give further views in the light of the group feedback until the group reaches a predetermined level of agreement. The judgements of those involved may be analysed statistically. See also Consensus methods.

- GDG (guideline development group) - The GDG is set up to consider the evidence and to develop the recommendations while taking into consideration the views of the external stakeholders. GDG members should include paediatricians (specialists and generalists), other child health professionals working in the area covered by the clinical guideline, and lay members.

- GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) - a transparent framework for developing and presenting summaries of evidence and provides a systematic approach for making clinical practice recommendations.

- Lay member - children and young people, parents or carers, representatives from patient organisations

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

- PICO framework (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) - a structured approach for developing review questions about interventions. The PICO framework divides each question into four components: the population (the population being studied), the interventions (what is being done), the comparators (other main treatment options) and the outcomes (measures of how effective the interventions are).

- Quality standards - set of specific, concise statements and associated measures. They set out aspirational, but achievable, markers of high-quality, cost-effective patient care, covering the treatment and prevention of different diseases and conditions.

- Quorum - The smallest number of group members that must be present to constitute a valid meeting.

- Scope - A document that describes what a piece of guidance will and will not cover. Depending on the type of guidance, organisations that are stakeholders, consultees or commentators can comment on the draft scope during a consultation period.

- Scope consultation table - A table of all the comments received during consultation on a scope, and responses to the comments.

- Scoping search - For guidelines, a search of the literature done at the scoping stage to identify previous clinical guidelines, health technology assessment reports, key systematic reviews and economic evaluations relevant to the guideline topic.

- Stakeholders - organisations or associations that have been identified by the GDG as having an interest in the clinical guideline topic, or who represent people whose practice or care may be affected directly.