While some recommendations describe organisational structures in England, services in the devolved nations are encouraged to adopt them to fit local models.

- Background

- Summary of updates

- Principles

- Summary flowchart

- Recommendations - Testing of children with lower respiratory tract infections (including bronchiolitis)

- Recommendations - Prior to presentation at hospital

- Recommendations - Presentation to ED or Paediatric Assessment Area

- Recommendations - Admission to paediatric ward / HDU

- Recommendations - Transfer to PICU

- Recommendations - Parents and carers

- De-escalating children with respiratory tract infections admitted to cubicles or cohort bays

- Guidance on escalating infection control processes

- Mitigating risk if these recommendations cannot be met

- Appendix 1: Hierarchy of controls

- Appendix 2: Aerosol generating procedures (AGPs)

- Appendix 3: Considerations for minimising transmission of respiratory infections in healthcare settings - standard Infection Control Precautions (SICPs)

- Appendix 4: Principles of room ventilation

- Appendix 5: Children at highest risk of severe infection

- Appendix 6: Example guidance on commencing and weaning from HFNCO

- Appendix 7: ED measles screening and streaming tool template

- Appendix 8: Audit tool on the management of children in hospital with viral respiratory tract infections (UK 2025)

- Methodology

- Downloads

Background

This is an update of the national guidance for the management of children in hospital with viral respiratory tract infections (2023).

Sustaining robust infection prevention and control (IPC) processes during periods of high circulation of viral respiratory tract infections is essential to keep patients, parents/carers and staff safe. It is important to learn from our experience during the COVID-19 pandemic so that we can maintain services and reduce the risk of transmission when faced with surges of RSV, influenza and other respiratory viruses. This includes consideration of the suitability of the estate, including ventilation, cleaning/disinfection protocols, and zoning arrangements as well as the application of isolation, cohorting, mask wearing and testing for respiratory viruses in the urgent and emergency acute unscheduled care pathway to ensure that we prevent avoidable infections due to respiratory viruses within hospital settings.

In the event of a large number of children presenting with viral respiratory tract infections causing bronchiolitis, viral induced wheeze or lower respiratory tract infections, it is important for both IPC and the operational flow of organisations to work collaboratively to ensure the safety of patients and staff, whilst maintaining capacity to provide care. However, it must be acknowledged that robust attempts must be made by staff and healthcare organisations to prevent avoidable infections with respiratory viruses because healthcare associated viral infections have worse clinical outcomes than community acquired infections and result in longer length of stay (LOS) including higher rates of PICU admissions. This significantly impacts patient flow across the entire hospital footprint.

Summary of updates

- SARS-CoV-2: Removal of SARS-CoV2 from the list of viruses that mandate isolation or virus specific cohorting. This is because of the cumulative evidence confirming that SARS-CoV 2 rarely causes severe respiratory tract infections in children.

- Duration of isolation: Although the current guidance still recommends the immunocompetent children with a viral respiratory tract infection are de-escalated from a cubicle/cohort bay after a period of 5 days following the onset of their symptoms, it is now recommended that children with influenza A or B who are either severely immunocompromised or requiring critical care management remain in a cubicle or cohort bay for at least 7 days following symptom onset; seek local IPC or virology advice due to risk of prolonged transmission.

- Measles: Due to measles still circulating in the UK (2025), guidance about children presenting with suspected measles continues to be included. An approach to screening for measles when a child presents to ED has been included (Appendix 7).

- Pertussis: Guidance about screening for pertussis has been included in the guidance due to its high infectivity and subsequent infection prevention repercussions and need for secondary prophylaxis for contacts.

- Implementation: A multidisciplinary group of stakeholders within each hospital (paediatrics, ED clinicians, IPC team, microbiology/virology, hospital management) should annually audit their practice/processes against the guidance within this document using the suggested audit tool (Appendix 8).

Principles

- The safety of patients and their families, and staff is paramount. Hospital acquired viral infections result in longer length of stay in children. In addition, nosocomial infection of staff impacts on staffing levels within hospitals. Both of these can significantly impact on the delivery of paediatric services within hospitals during periods of high viral prevalence. In addition to maintaining robust IPC practices, vaccination of staff, children and pregnant women against vaccine preventable respiratory tract infections (influenza, pertussis and RSV) should be optimised.

- Despite putting the measures outlined within this guidance in place to prevent avoidable infections in hospital, it should be recognised that transmission of respiratory viruses in hospital settings will still occur. For this reason, one of the main strategies should be to protect the most vulnerable children when they present to hospital. During periods of high viral prevalence, cubicles (in ED settings, short stay units and inpatient wards) should be prioritised for children at the highest risk of severe disease (see Appendix 5). In addition to these children being the highest risk for subsequent admission to PICU and prolonged hospital stays, they are also the largest risk for asymptomatic carriage and prolonged viral excretion; isolating them also protects other children from infection.

- Although an evidence-based pragmatic approach has been adopted in the development of this guidance, it is acknowledged that recommendations will evolve with experience. It is also recognised that, in the event of single room capacity being exceeded or testing capacity being limited, it may not be possible to adhere to this guidance in its entirety. In this situation, a local risk assessment involving paediatricians, IPC staff, microbiology/virology staff and hospital managers needs to be conducted. This local risk assessment needs to be regularly reviewed as cases of viral respiratory tract infections increase significantly. For guidance, see NHSE criteria for completing a local risk assessment: acute inpatient settings and NHSE isolation tool.

- The estates that children are managed in and the support available to implement IPC practices vary considerably between hospitals; adopting the hierarchy of controls, which are applied in order of impact (See Appendix 1) will identify the most appropriate and effective measures to prevent avoidable infections. Hospitals should annually audit the processes they have in place against the guidance within this document using the suggested audit tool (Appendix 8).

- The personal protective equipment (PPE) recommendations within this guidance are based on the principles outlined in the National infection prevention and control manual for England. These principles should be adopted by all staff looking after children with suspected and confirmed viral respiratory tract infections and the choice of PPE should be in accordance with transmission-based precautions:

- FFP3 mask / respirator, eye protection, apron (gown if disposable apron provides inadequate cover for the procedure or task being performed) and gloves should be worn during aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) on children with known or suspected respiratory infections. The respirator must meet the requirements of the individual wearing it, ie FFP3 fit testing. The definition of AGPs was amended following a rapid review of AGPs conducted in June 2022 (See Appendix 2). High-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNCO) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) are no longer considered AGPs. However, open suctioning beyond the oro-pharynx, such as in children with tracheostomies is still considered an AGP. Staff managing children with tracheotomies who are symptomatic for viral respiratory tract infections should wear appropriate PPE (FFP3 and eye/face protection or Respirator/Hood with a visor if the risk assessment suggests a splash is likely) during open suctioning or whilst performing other AGPs.

- Even if AGPs are not being performed, the choice of PPE (apron/gown, mask/respirator, eye protection and/or gloves), should be based on an assessment of the patient´s symptoms, duration of clinical encounter, proximity to the patient and risk associated with the clinical procedure being performed or if an unacceptable risk of transmission remains following application of the hierarchy of controls. Appropriate PPE should be worn by all staff in a cohort area if AGPs are performed on any of the children being managed within that cohort bay.

- Hand hygiene must be performed immediately before and after patient contact. During periods of high prevalence of respiratory viruses, universal masking should also be considered as part of a local PPE risk assessment.

- The environment within which children with viral respiratory tract infections are managed should be compliant with national recommendations. Steps should be taken to reduce the risk of virus transmission in areas that are crowded and/or poorly ventilated. These might include systems for segregating isolating patients who are particularly vulnerable from those who may have infection, reducing the occupancy of the area, enhancing ventilation or adding air cleaners (See Appendix 3). All patient areas, including waiting areas and cohort bays, should have adequate ventilation (minimum 6 air changes per hour) (See Appendix 4)

- To optimise flow through the hospital, isolation / cohorting should be stepped down in a timely manner. For the majority of children, de-escalation should be performed 5 days after the onset of symptoms. For children with influenza A or B who are either severely immunocompromised or requiring critical care management (PICU), de-escalation from a cubicle / cohort bay should only be considered 7 days after symptom onset; seek local IPC or virology advice due to risk of prolonged transmission.

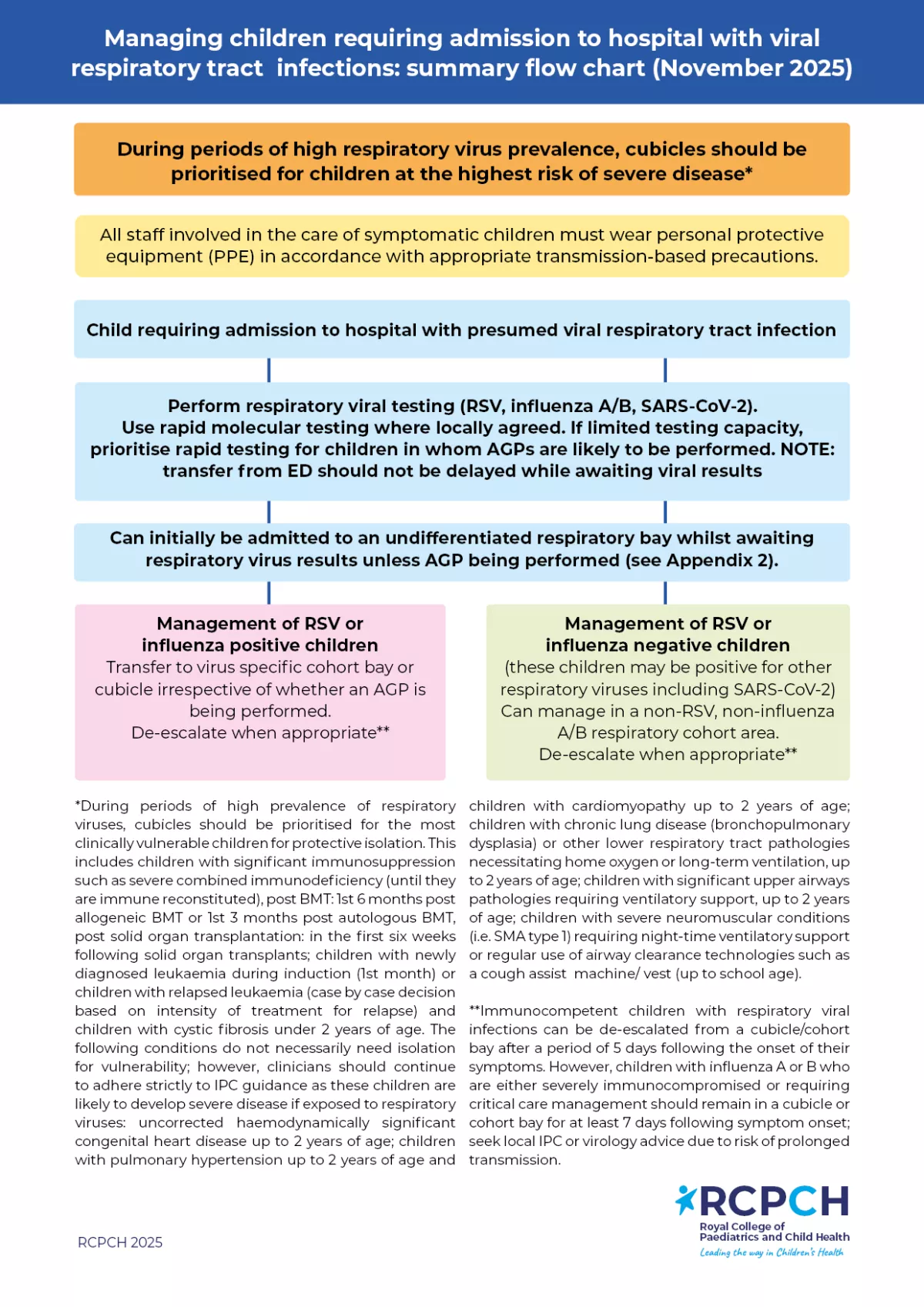

Summary flowchart

- Expand to view summary flowchart - updated November 2025

-

You can also download this summary flowchart as an A4 poster below.

Recommendations - Testing of children with lower respiratory tract infections (including bronchiolitis)

- Children being admitted with symptoms consistent with a viral respiratory tract infection should have access to a point of care (POC) molecular test or rapid laboratory based molecular test (RSV, Influenza A/B and SARS-CoV-2). Children should have parity with adults in terms of access to diagnostic tests. Access to rapid respiratory virus results will enable timely commencement of antiviral treatment (if indicated) as well as informing robust IPC practices. Only children being admitted require testing for respiratory viruses. However, during periods of increased influenza prevalence, influenza testing should be performed in high-risk children being discharged from ED (ideally in whom symptoms began in the preceding 48 hours). The definition of high risk should be based on UK HSA influenza treatment guidance (children with neurological, hepatic, renal, pulmonary or chronic cardiac disease; diabetes mellitus; severe immunosuppression; children under 6 months of age or morbid obesity (BMI ≥40)); a timely diagnosis of influenza would result in treatment being initiated in this cohort of children and may avoid subsequent admission.

- Very few EDs have sufficient capacity to keep large numbers of children in their department awaiting virology results. Transfer of a child from ED to a short stay or inpatient setting including escalation to critical care units should not be delayed whilst awaiting a test result. However, testing should be performed in ED where indicated, and processes should be in place to minimise the turnaround time of results.

- Further extended respiratory panel testing for a broader range of pathogens should only be considered if the results will influence the management of the patient (ie facilitating early cessation of antibiotics or guiding IPC measures for extremely vulnerable patients).

Recommendations - Prior to presentation at hospital

- As part of system level (ICB) planning for winter viral surges, key leaders including paediatric respiratory input should collaborate to encourage alignment of pathways across NHS 111, primary care, UTCs and EDs to ensure consistent management strategies across the entire urgent care pathway. Agreed pathways should ensure that children with mild bronchiolitis and lower respiratory tract infections are managed in primary care settings where possible in order to reduce the number of infants and children with respiratory symptoms presenting to hospital. Planning should include the implementation of locally appropriate integrated models of care, enabling secondary care clinicians to support primary care colleagues. The expectation should be that children with mild and moderate bronchiolitis or viral induced wheeze are initially reviewed in primary care settings and guidance is provided to parents about when to seek a healthcare consultation. An example of this includes:

- Examples of clinical pathways supporting the management of children with shortness of breath by clinicians in primary care settings include the following:

- Clinicians should have access to paediatric oxygen saturation monitor probes in primary care settings.

- Uptake with preventive treatment as per national guidance including influenza vaccines in children (including long term hospital stay patients), as well as RSV, influenza and pertussis-vaccination in pregnant women and nirsevimab for children aged under 23 months that meet the criteria as specified in the Green Book should be optimised. Children with risk factors for severe influenza outside of the ages of routine immunisation (6 months to 2 years) should be actively identified and influenza vaccination promoted. Efforts should be made to optimise influenza vaccine uptake rates in all staff caring for children.

- Due to measles once again circulating in the UK (Oct 2025), immunisation status should be checked on all children presenting to hospital and MMR vaccination promoted for all unimmunised children aged >12 months (including 2nd MMR vaccine in children aged >3 years and 4 months). During periods of increased measles circulation, information should be disseminated to primary care colleagues to reduce the risk of such patients unnecessarily presenting to hospital.

Recommendations - Presentation to ED or Paediatric Assessment Area

- There is no evidence to support the practice of separating paediatric emergency departments into hot and cold areas. This is because of the potential of asymptomatic transmission in ‘cold’ areas; isolation of the most vulnerable children is a far more effective strategy during periods of high prevalence of respiratory viruses.

- Prompt triage of patients, enabling adequate physical distancing, encouraging respiratory and hand hygiene are all important measures for reducing the risk of nosocomial infection during periods of increased circulation of respiratory viruses. Reception and triage staff should encourage parents/carers who are symptomatic to wear fluid resistant surgical masks. Regular environmental cleaning should be performed according to National standards of healthcare cleanliness 2025 or if IPC recommendations differ due to new and emerging evidence.

- Due to low MMR vaccine uptake in children, measles is once again circulating in the UK (2025) – if an unimmunised child presents with symptoms of measles (fever PLUS suggestive rash (blotchy, red-brown rash that usually starts on the face and behind the ears, then spreads to the rest of the body, made up of flat or slightly raised spots that may merge into larger patches and is usually not itchy which appears about 2 to 4 days after initial symptoms) PLUS one of: coryza, cough, conjunctivitis), immediately isolate, perform testing as per national guidance and wear appropriate PPE. Epidemiological factors that increase the likelihood of a measles diagnosis include:

- UNVACCINATED

- Age: measles more likely in teenagers/young adults with typical clinical presentation than in younger children

- Contact with confirmed or strongly suspected case of measles (infectious from 4 days before the onset of symptoms to 4 days after).

- Member of under-vaccinated community

- Travel to area where measles is circulating

- Attendance at mass gathering event

- Partially vaccinated (although 95% protection following 1 dose of MMR)

- During periods of increased circulation of measles, local processes should be put in place at all points where children are triaged on arrival to hospital (See Appendix 7 for a measles screening and streaming tool template developed by Alder Hey Children’s Hospital). NOTE: this tool should be adapted for local use following discussion with local infection specialists (paediatrics, IPC, virology)

- The possibility of pertussis should be considered in all babies and children presenting to hospital with respiratory tract symptoms. Consider displaying the RCPCH pertussis poster in reception and triage areas. Symptoms of pertussis include coughing spasms associated with:

- Worsening severity

- A gasping sound or ‘whoop’

- Difficulty in breathing

- Change in colour of the face

- However, in young infants, the typical ‘whoop’ may never develop and coughing spasms may be followed by periods of apnoea. In older children and adults, the disease may present as persistent cough without these classic features. A pertussis risk assessment should be based on symptoms as well as vaccine history (maternal vaccine history if baby <3 months), especially in a baby/child in whom an alternative viral aetiology has been excluded.

Recommendations - Admission to paediatric ward / HDU

- Patients with viral respiratory tract infections (apart from those at the highest risk of severe disease) can be admitted into an undifferentiated respiratory cohort area until their virology results are available.

- The implementation of a cohort area should be underpinned by a local risk assessment that takes into consideration the hierarchy of controls (see Appendix 1). These include:

- use of curtains/screens where possible

- adherence with IPC procedures by parents/carers (use of a fluid resistant surgical mask if symptomatic and daily symptom checks, and complying with hand hygiene)

- review of ventilation of the bay and mitigation strategies (see Appendix 4). Advice can be sought from the Ventilation Safety Group which is part of the Trust governance structures.

- environmental cleaning as specified within the National standards of healthcare cleanliness 2025.

- Children at the highest risk of severe disease (See Appendix 5) should be prioritised to a cubicle (irrespective of symptoms) to reduce the risk of nosocomial infection (these children are also the largest risk for asymptomatic carriage and prolonged viral excretion so isolating them also protects other children from infection). Clear signage must be displayed outside the cubicle to inform staff about appropriate PPE requirements. If single room capacity is limited, a local risk assessment needs to be conducted. If they are admitted with a viral respiratory tract infection, a risk assessment should be performed when their test results are available to help decide whether they are subsequently transferred into a virus specific cohort bay or remain in a cubicle.

- Once virology results are available, it is best practice to cohort (or isolate) children with RSV or influenza to minimise risk of nosocomial infection. This assumes that the environmental ventilation and geographical layout of the cohort area permits this (to avoid nosocomial infection beyond the cohort bay). If this is not possible, then a documented organisational local risk assessment should be undertaken including the hierarchy of controls to minimise and mitigate the risk of healthcare associated (nosocomial) infection (see Appendix 1).

- If a child is negative for RSV and influenza A/B, they do not need to be managed in a cubicle but ideally in a non-RSV, non-influenza A/B respiratory cohort area, irrespective of whether they are positive for another respiratory virus. This includes children with confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Children at highest risk of severe disease (see Appendix 5), should not be admitted to an undifferentiated respiratory bay.

- Staff looking after children in this cohort area (or in a cubicle) must apply appropriate transmission-based precautions and appropriate Respiratory Protective Equipment (RPE) (surgical face mask and eye protection) unless AGP being performed (see Appendix 2) in which case aerosol PPE is required – as per national IPC manual.

- If high-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNCO) is initiated, a clear plan should be in place to promote appropriate weaning (see Appendix 6). HFNC should be reviewed at least daily with a documented plan for weaning and discontinuation, rather than being continued by default once started.

- Immunocompetent children with respiratory viral infections can be de-escalated from a cubicle/cohort bay after a period of 5 days following the onset of their symptoms. However, in children with influenza A/B who are either severely immunocompromised or requiring critical care management, de-escalation should only be considered after 7 days following symptom onset; seek local IPC or virology advice due to risk of prolonged transmission.

- If a child develops new symptoms / signs consistent with a respiratory viral infection during their admission, urgent testing should be undertaken along with review that appropriate transmission-based precautions are in place.

- Discharge of children with bronchiolitis from an inpatient setting should be considered when:

- They are clinically stable

- They are taking adequate oral fluids

- They are maintaining oxygen saturation in air at the following levels for 4 hours, including a period of sleep:

- over 90%, for children aged 6 weeks and over

- over 92%, for babies under 6 weeks or children of any age with underlying health conditions. (NICE guidance: Bronchiolitis in children (Aug 2021)

Recommendations - Transfer to PICU

- Virology samples should be sent from the referring hospital / ED, where possible. A point of care molecular test or laboratory based rapid molecular test should be performed in the local hospital if routine laboratory results are not available.

- Members of the retrieval team should adhere to appropriate transmission- based precautions / PPE. The decision to wear an FFP3 respirator/hood should be based on clinical risk assessment, eg task being undertaken, the presenting symptoms, the infectious state of the patient, risk of acquisition and the availability of treatment.

- During periods of high viral prevalence and large numbers of children requiring admission to PICU, a child who requires repatriation from PICU to a local hospital should be given priority over an elective admission to facilitate flow of severely unwell children into and out of PICU. Patient placement advice should be provided to the receiving organisation based on the respiratory virus, test results and other pathologies / clinical conditions.

- Children being discharged to a general paediatric ward or repatriated to a local hospital from PICU do not require a negative viral result in order to step down onto a ward non-isolation area. Admission into a cubicle or cohort area is only required if the patient is still deemed infectious or there are other reasons for source or protective isolation.

Recommendations - Parents and carers

- Staff looking after children should perform a daily symptom check on parents/carers. Resident carers should not be in the hospital if they have respiratory symptoms. If parents/carers are symptomatic and need to remain in the hospital, they should wear a fluid resistant surgical mask in communal areas including within a cohort bay. Symptomatic parents in cubicles should wear a fluid resistant surgical mask when staff are in the cubicle.

- Siblings should not visit if they are symptomatic.

- Education and written information for resident carers should be made available regarding respiratory viruses, local policies, and use of communal facilities, fluid resistant surgical masks, hand hygiene, PPE and physical distancing.

De-escalating children with respiratory tract infections admitted to cubicles or cohort bays

Immunocompetent children with respiratory viral infections can be de-escalated from a cubicle/cohort bay after a period of 5 days following the onset of their symptoms.

Children with influenza A or B who are either severely immunocompromised or require critical care management should remain isolated in a cubicle or managed within an influenza cohort bay for at least 7 days following symptom onset; seek local IPC or virology advice due to risk of prolonged transmission (Morris SE et al. Influenza virus shedding and symptoms: Dynamics and implications from a multiseason household transmission study. PNAS Nexus. 2024).

Guidance on escalating infection control processes

In the event of confirmed outbreaks within paediatric units involving staff, parents or children, escalation of infection control processes may need to be considered including some or all of the following mitigations:

- Ensure infection control measures in hospital (eg use of fluid resistant surgical masks by parents/carers, hand hygiene) are being actively encouraged and monitored

- Consider limiting visiting to one parent/carer for duration of admission (or swapping weekly) or introducing tighter restrictions on visitors, such as limiting the frequency of changeover of resident parents/carers and restricting visitation by siblings

- Daily screening of symptoms in resident parents/carers

Additional measures may need to be considered during periods of high local prevalence of respiratory viruses in conjunction with local infection prevention and control teams.

Mitigating risk if these recommendations cannot be met

It is acknowledged that there is considerable variation between hospitals in terms of isolation capacity (single rooms), turnaround times for respiratory virus PCR results and access to respiratory virus panels. This may make it extremely challenging to comply with the recommendations made within this document whilst maintaining flow of patients.

In this situation, a local risk assessment needs to be conducted based on IPC principles, the hierarchy of controls and relative risks (see Appendix 1). Weighing up of various factors including patient factors (extreme vulnerability, continuation of AGPs), staff factors (vulnerability of staff working within cohort areas), environmental factors (ventilation of cohort areas, distance between bed-spaces), respiratory virus prevalence rates and access to testing (turn-around time for respiratory viral PCR testing) is required.

It is recommended that a multidisciplinary approach is adopted (including medical, nursing, operations and IPC teams) in order to collaboratively develop clinical pathways and contingencies based on local risk assessments. This risk assessment needs to be regularly reviewed, especially as the number of respiratory virus admissions increases. In addition, if virology samples are sent to regional virology units, it is recommended that discussions about prioritisation of paediatric samples and access to rapid test results takes place.

Appendix 1: Hierarchy of controls

- Expand to view Appendix 1

-

Controlling exposures is the fundamental method of protecting patients and staff from nosocomial infections. A hierarchy of controls is used as a means of determining how to implement feasible and effective IPC measures:

Appendix 2: Aerosol generating procedures (AGPs)

- Expand to view Appendix 2

-

Aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) are medical procedures that can result in the release of aerosols from the respiratory tract. The criteria for an AGP are a high risk of aerosol generation and increased risk of transmission (from patients with a known or suspected respiratory infection).

The list cited in the National Infection Control Manual includes the following (but local policy may vary):

- awake* bronchoscopy (including awake tracheal intubation)

- manual ventilation via endo-tracheal tube (ETT) or tracheostomy if open circuit, eg Ayres T-piece without a filter or NIV via tracheostomy on a single limb circuit

- awake* ear, nose, and throat (ENT) airway procedures that involve respiratory suctioning

- induction of sputum

- respiratory tract suctioning**

- surgery or post-mortem procedures (like high speed cutting / drilling) likely to produce aerosol from the respiratory tract (upper or lower) or sinuses

- tracheostomy procedures (insertion or removal).

*Awake including ‘conscious’ sedation (excluding anaesthetised patients with secured airway)

** The available evidence relating to respiratory tract suctioning is associated with ventilation. In line with a precautionary approach, open suctioning of the respiratory tract regardless of association with ventilation has been incorporated into the current (COVID-19) AGP list. It is the consensus view of the UK IPC cell that only open suctioning beyond the oro-pharynx is currently considered an AGP, that is oral/pharyngeal suctioning is not an AGP.

For complete list of AGPs, see NHS England » Aerosol generating procedures & A rapid review of aerosol generating procedures (AGPs). An assessment of the UK AGP list conducted on behalf of the UK IPC Cell. Version 2.0, 7 February 2022

Staff should be fit tested and provided with the appropriate training for the correct use of respiratory protective equipment (RPE). Current guidance is that an FFP3 respirator must be worn by staff when caring for patients with a suspected or confirmed infection spread by the airborne route, when performing AGPs on a patient with a suspected or confirmed infection spread by the droplet or airborne route, and when deemed necessary after risk assessment. It may be necessary to consider the extended use of an FFP3 mask for patient care in specific situations, such as prolonged and close exposures to infectious patients.

Appendix 3: Considerations for minimising transmission of respiratory infections in healthcare settings - standard Infection Control Precautions (SICPs)

- Expand to view Appendix 3

-

Increasing evidence suggests that many respiratory diseases are spread through the inhalation of particles that carry pathogens that have been released into the air by an infected person. This may be through breathing, coughing, talking or in some cases via an aerosol generating procedure. Particles in the air can be a range of different sizes and can stay in the air from a few seconds to hours depending on their size and the ventilation in a room. Exposure is always riskier at close proximity to an infected person, however there is evidence for transmission when sharing the same room or even between rooms for a number of diseases.

The risk of transmission of airborne respiratory viruses is highest when any of the three C’s are present:

- Crowded places

- Close contact

- Confined and enclosed spaces with poor ventilation

Other factors which affect the risk of transmission are the number of people in the room who are infected, the amount of viruses they are expelling (which may be influenced by the stage of their infection and their behaviour, eg coughing, talking), the length of time a person is present in the room, and whether the masks are being worn to reduce virus emission and inhalation.

Areas that meet any of the three C’s criteria should be identified and steps taken to mitigate the risk of virus transmission especially during periods of high prevalence. These might include establishing systems for segregating patients who are symptomatic or who are known to be infected, reducing the occupancy of spaces to enable people to maintain distance, enhancing ventilation or adding air cleaners, using masks as a source control where possible, and using respiratory protection for all those present in the area who may be susceptible to infection.

Appendix 4: Principles of room ventilation

- Expand to view Appendix 4

-

Ventilation means the process of providing fresh (outdoor) air into a room or building and can be provided by mechanical methods (using fans and ducts) and/or by the passive flow of air through openings (windows, doors, or vents) – known as natural ventilation. Air conditioning is the process of cooling, heating, and humidifying air and although it may be linked to ventilation and provide outdoor air as well as controlling the building environment; in many spaces air conditioners simply recirculate the same air.

The movement of air through indoor spaces helps to reduce the risk of transmission by dispersing and diluting virus particles in the air. Assuming the air in a room is reasonably well mixed, the ventilation rate can be expressed as air changes per hour (ACH) which is equivalent to air flow in m3/hour divided by the room volume (height x width x depth). Ventilation can also be expressed in terms of the amount of air per person, which is normally litres per second per person (l/s/p).

A ventilation rate of at least 6 ACH in general healthcare areas is preferred to minimise the risk of transmission of airborne viruses (NHS England » (HTM 03-01) Specialised ventilation for healthcare buildings). Ventilation rates in source isolation rooms should be 10 ACH under negative pressure. In non-clinical areas such as offices and break rooms at least 10 l/s/p based on normal maximum occupancy is recommended. These can be achieved by either mechanical or passive ventilation in office setting and mechanical ventilation in clinical settings.

- Environmental mechanical ventilation provides more reliable and consistent ACH provided the system is well designed and maintained. Hospital mechanical ventilation systems in UK hospitals should be full fresh air without recirculation; any recirculation should be minimised unless the system is specifically designed with infection control measures (filters or UV disinfection) in place to prevent reintroduction of pathogens via the ventilation system.

- Natural ventilation is less reliable as the airflow rate depends on the weather and it often relies on staff or patients remembering to open windows. It may not be an available option in some rooms, and in cold, windy or wet weather may only be possible for short periods. Opening two or more windows on opposite sides of the room helps to create cross ventilation and improve dilution and dispersion. Because natural ventilation is determined by the external weather conditions, particularly the wind, it can sometimes create unwanted airflows between rooms. It is not recommended for isolation rooms, ICU or in other settings where patients are known to have an infection that is transmissible via an airborne route or where susceptible patients are very vulnerable.

- Air cleaners (purifiers or scrubbers) are local air circulators which draw air through filters and/or over UVC lamps to remove particles and release clean air. They can be used to enhance ventilation in areas with poor air changes. Devices can be portable plug in units, or semi-permanent devices fixed to walls or ceilings. They should be placed in spaces where ventilation rates are lowest and not close to ducts/grills or opening windows/doors, or where they may be a trip hazard. They should also ideally be at least 1m from the patient. They are most effective when operated using the highest fan speed, but this may generate significant noise. Units should be specified with clean air flow rates, noise, size and maintenance considerations in mind.

- When fans or air conditioners are used, it is critical to ensure that there is also an adequate fresh air ventilation supply, as these devices simply manage comfort and do not provide any ventilation or infection control. Electric fans and recirculating air conditioners to manage thermal comfort can be used during hot periods, but should be used with care. Fans should be easy to clean and not have internal parts which can harbour pathogens. Fans should be positioned so that they don’t move air between two rooms or so that they don’t move air directly from one person to another. Air conditioning units should also be positioned so they don’t create unwanted air paths between people and should be well maintained with regular filter changes.

- Useful references/further information for Appendix 4

-

WHO (2021) Roadmap to improve and ensure good indoor ventilation in the context of COVID-19

NHS Estates Health Technical Memoranda.

NHS England Specialised ventilation for healthcare buildings

Appendix 5: Children at highest risk of severe infection

- Expand to view Appendix 5

-

Children vulnerable to severe disease if infected with respiratory viruses should be prioritised to a cubicle (protective isolation). These include:

- Children with significant immunosuppression such as severe combined immunodeficiency (until they are immune reconstituted), post BMT: 1st 6 months post allogeneic BMT or 1st 3 months post autologous BMT, post solid organ transplantation: in the first six weeks following solid organ transplants; children with newly diagnosed leukaemia during induction (1st month) or children with relapsed leukaemia (case by case decision based on intensity of treatment for relapse).

- Children with cystic fibrosis aged under 2 years of age.

The following conditions do not necessarily need isolation for vulnerability, however, clinicians should continue to adhere strictly to IPC guidance as these children are likely to develop severe disease if exposed to respiratory viruses:

- Children with uncorrected haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease up to 2 years of age; children with pulmonary hypertension up to 2 years of age and children with cardiomyopathy up to 2 years of age.

- Children with chronic lung disease (bronchopulmonary dysplasia) or other lower respiratory tract pathologies necessitating home oxygen or long-term ventilation, up to 2 years of age

- Children with significant upper airways pathologies requiring ventilatory support, up to 2 years of age.

- Children with severe neuromuscular conditions (ie SMA type 1) requiring night-time ventilatory support or regular use of airway clearance technologies such as a cough assist machine/vest (up to school age).

Appendix 6: Example guidance on commencing and weaning from HFNCO

Courtesy of North and South Thames Paediatric Networks and retrieval services and the British Paediatric Respiratory Society

HFNCO is an escalation step for children with significant respiratory distress or hypoxaemia and is not a substitute for timely NIV or intubation where there are red flags for impending respiratory failure. Every child started on HFNCO should have a clear plan for review, escalation and weaning.

- Expand to view Appendix 6

-

Commencing treatment

- HFNC should only be started where there is a clear physiological indication and appropriate nursing and medical oversight (i.e. a high-dependency level of care), rather than as a default response to tachypnoea.

- Select interface and equipment based on local availability and patient age and weight. Interface size should not exceed 50% of nares. If flow rate according to weight cannot be achieved on the correct interface, then use maximum flow for interface.

- On initiation a competent clinician should observe the patient for comfort and compliance. If necessary the flow can be increased to reach the maximum recommended range according to weight, over a five- minute period.

- Monitoring – a senior paediatrician (ST4+/equivalent) should review the child within 1 hour of starting HFNCO and at least 4-hourly while on HFNCO at high-dependency level care, with a documented plan to escalate or wean at each review.

- Titrate FiO2 to maintain SpO2 >92% (or alternative patient range).

- Escalate or wean. To avoid rapid deterioration or unnecessary continuation on HFNCO, review response to HFNCO and follow the escalation or weaning criteria below. NOTE: once FiO₂ has been reduced to around 0.3–0.4 and the work of breathing is improving, the default should be to halve the flow and aim to discontinue HFNC within the next 4–6 hours, unless there are clearly documented reasons to continue.

<12 kg 2 l/min/kg 13-15 kg 20-30 l/min 16-30 kg 25-35 l/min 31-50 kg 30-40 l/min >50 kg 40-50 l/min

Avoid prolonged use of non–weight-based, low HFNCO flows (for example 2–4 L/min in larger children). Once FiO₂ is low and the child is improving, it is usually better to trial off HFNCO than to continue on subtherapeutic flows.

Response to treatment

Sustained response to HFNCO

Nursing ratio 1:4 or 1L3 <2 years

Response to HFNCO

Nursing ratio 1:2 or 1:3 if cohort is ward level

Unresponsive to treatment

Wean FiO2 to 0.3-0.4 (depending on patient) Moderate respiratory distress continues

and/or FiO2>0.4-0.6In the first hour - Once FiO₂ has been weaned to ≤0.4 and work of breathing has improved, start weaning the flow

- Halve the flow rate (keeping within the weight-based range for age/weight).

- If the child remains stable for 1–2 hours (PEWS unchanged, no increase in work of breathing, SpO₂ in target range), stop HFNCO completely and observe closely for 60 minutes (a short “HFNC holiday” / trial off)

- If they remain stable off HFNC, do not restart high-flow; use low-flow oxygen if needed

- If they deteriorate, restart at the last tolerated flow and reassess for red flags/escalation

- Re-assess essential care considerations** and continue on current HFNCO settings until ready to wean

THEN - Continue to observe for any deterioration or red flags*

- Re-assess essential care considerations**

- Ensure paediatric consultant has reviewed the patient

- Discuss with the retrieval service

- Discuss/review with the anaesthetic registrar

- Closely observe for any red flags*

After 2nd hour or with any red flags*:

- Consider NIV or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)

- Prepare patient, team and family for intubation

*Red flags for immediate escalation

Immediate reaction

- Any apnoeic/bradycardic episodes

- Increasing respiratory distress after HFNCO commenced

- Clinically tiring

- The Paediatric Early Warning System (PEWS) indicates immediate escalation to resus team

- FiO2 >0.6

- Increase FiO2 to maximum

- Call 2222

- Prepare for intubation

- Liaise with retrieval team or on-site Level 3 paediatric critical care

- Communicate with the family

Monitoring and patient management (with corresponding patient acuity)

- Continuous oxygen saturations (green, amber, red)

- Observation frequency and escalation according to PEWS (green)

- Minimum hourly observations and escalation according to PEWS (amber, red)

- Consider continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) if required (amber, red)

- 2 hourly mouth and nose care including pressure area check (green, amber, red)

- Hourly documentation of FiO2, flow rate, and temperature as well as equipment specific checks (green, amber, red)

** Essential care considerations

- Optimised positioning (eg head elevation).

- Consider referral for physiotherapy assessment.

- Secretion clearance if indicated and safe to do so.

- Consider feeding regime alteration according to risk and underlying disease:

- High risk (red) should be nil by mouth (NBM) with intravenous fluids.

- Medium risk (amber) should be assessed before feeding and fed with caution.

- Psychosocial support, clear communication, play and distraction.

- Minimal handling / cluster cares.

- Blood gas analysis not essential and acidosis is a late sign of failure.

Patient transfer

If patient transfer is required, then a suitable risk assessment tool should be used. Examples include the safe transfer of paediatric patients (STOPP) tool. Where portable HFNCO is not available, a senior clinician should assess the appropriate oxygen delivery based on direct patient assessment.

Appendix 7: ED measles screening and streaming tool template

- Expand to view Appendix 7

-

This resource is from Alder Hey Children's Hospital. You can also download this below as a PowerPoint.

Appendix 8: Audit tool on the management of children in hospital with viral respiratory tract infections (UK 2025)

- Expand to view Appendix 8

-

Purpose: To assess compliance with the 2025 national guidance on the management of children in hospital with viral respiratory tract infections

Scope: Applies to Emergency Department (ED), Paediatric Assessment Units (PAU), Paediatric Wards, HDU, PICU, and IPC teams

Download the audit toolkit PDF and Excel resources below. Please note the MS Excel file may not open in Google Chrome or other web browsers. If this happens, click or tap the file in the Downloads section, then check your browser's Downloads and then opt to download the file.

Methodology

- This guidance was updated in October 2025 in consultation with the following clinical advisory group members:

-

- Chair - Sanjay Patel, Consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Southampton Children’s Hospital

- NHSE CYP team – Simon Kenny

- NHSE IPC team – Fiona Hammond

- Paediatric infectious diseases – Alejandra Alonso, Consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Evelina London Children's Hospital; Beatriz Larru - Director of Infection Prevention & Control, Infection Control Doctor, Alder Hey Children's Hospital

- PICU – Ruchi Sinha, National Specialty Adviser (NSA) Paediatric Critical Care

- Virology / microbiology - Sarah Thompson, Consultant microbiologist and Director of Infection Prevention & Control, Sheffield Children's Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

- The previous guidance was updated in October 2023 in consultation with the following clinical advisory group members:

-

- Chair: Dr Sanjay Patel. Paediatric Infectious Diseases Consultant. Southampton Children’s Hospital

- Helen Dunn, Consultant Nurse Infection Prevention & Control and Director of Infection Prevention & Control (DIPC), Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust

- Dr Liz Whittaker, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Consultant, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Fiona Hammond, IPC Improvement Lead, National Infection Prevention and Control Team, NHS England

- Carole Fry, Lead for Infection Prevention and Control, UK Health Security Agency

- Dr Beatriz Larru Martinez, Consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases and Director of Infection Prevention & Control, Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust

- Samantha Matthews, National Clinical Lead (Infection Prevention & Control Programme), NHS England

- Sarah Thompson, Consultant microbiologist and Director of Infection Prevention & Control, Sheffield Children's Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

- Professor Jennie Wilson, President, Infection Prevention Society, University of West London

- Dr Conor Doherty, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Consultant, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde

- Dr Danielle Eddy, Paediatric Specialty Trainee, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

- Dr Ian Maconochie, Paediatric ED consultant, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Dr Ian Sinha, Paediatric Respiratory Consultant, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

- Dr John Criddle, Paediatric ED Consultant, Evelina London Children's Hospital

- Dr Julian Legg, Lead for Paediatric Respiratory Medicine, Southampton Children’s Hospital

- Dr Matthew Clarke, NHSE National Specialty Advisor for Children and Young People

- Dr Padmanabhan Ramnarayan, PICU Consultant, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Dr Paul Randell, Consultant Virologist, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Dr Poonamallee Govindaraj, Paediatric Consultant, Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board

- Dr Raymond Nethercott, General Paediatric Consultant and RCPCH Officer for Ireland

- Dr Ruchi Sinha, PICU Consultant, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

- Samantha Matthews, NHSE/I Infection Prevention & Control National Clinical Lead

- Dr Sean O’Riordan, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Consultant, Leeds Children’s Hospital

- Professor Simon Kenny, NHSE National Clinical Director for Children and Young People