What was the challenge?

Winter brings a host of issues in a hospital, the most extreme of which is crowding. This results from the combination of high inflow (with at times high acuity) and poor outflow (ie delays in transferring patients to wards). This creates double jeopardy as the longer patients spend waiting in the department for a hospital bed, the more work for staff in the department. This reduces staff's ability to process new cases and provide treatments. High inflow without outflow obstruction can be challenging but does not result in the patient safety and resource issues that crowding creates.

These challenges are not just confined to emergency medicine; bed occupancy and staffing levels will also impact on paediatrics assessment units linked to, or geographically separated from, Emergency Departments. The principles, and our approaches, are probably relevant to all aspects of acute care.

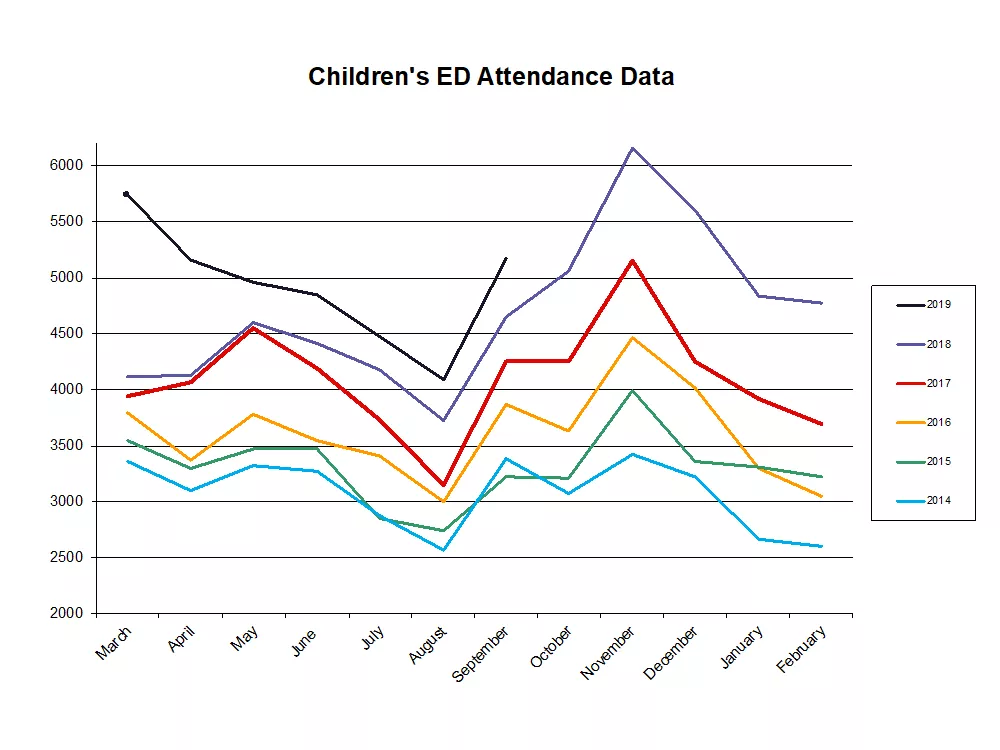

Our data accurately predict these times of challenge, almost to the day - and November is consistently the most challenging month of the year. This helps us in being able to plan responses, but year-on-year growth in attendances definitely creates winter fatigue (even before winter), and is not sustainable.

What did you do?

Our main intervention was to develop a common strategy to be used at times of escalation and major incident (available below). Sadly an OPEL (operating pressures escalation level) 3 or 4 status can persist for weeks in the winter, and escalation fatigue is not different from alarm fatigue.

We released short guides to dealing with specific issues of:

- high inflow

- poor outflow

- high acuity

- reduced staffing, and

- the combined result of overcrowding.

These were discussed at team meetings and in teaching sessions.

Using your space effectively is very important, and we reconfigure bed use at times of escalation so that minors becomes 'one in and one out' as cubicle space is taken over by majors. It is vital at times of high demand that cubicle space be used wisely so that the undertaking of interventions such as fluid challenges and post inhaler observations can take place in waiting room areas. Blocking cubicles unnecessarily will impact on safety in the department, simultaneously acknowledging this may be a less pleasant experience for the family (see guide for more details, link below).

We often note it is important to acknowledge that senior presence alone can effect changes in behaviour and alleviate anxiety.

What impact did it have?

Evidencing the impact our interventions is challenging as the time periods in which they are most used are the periods in which our performance is most challenged.

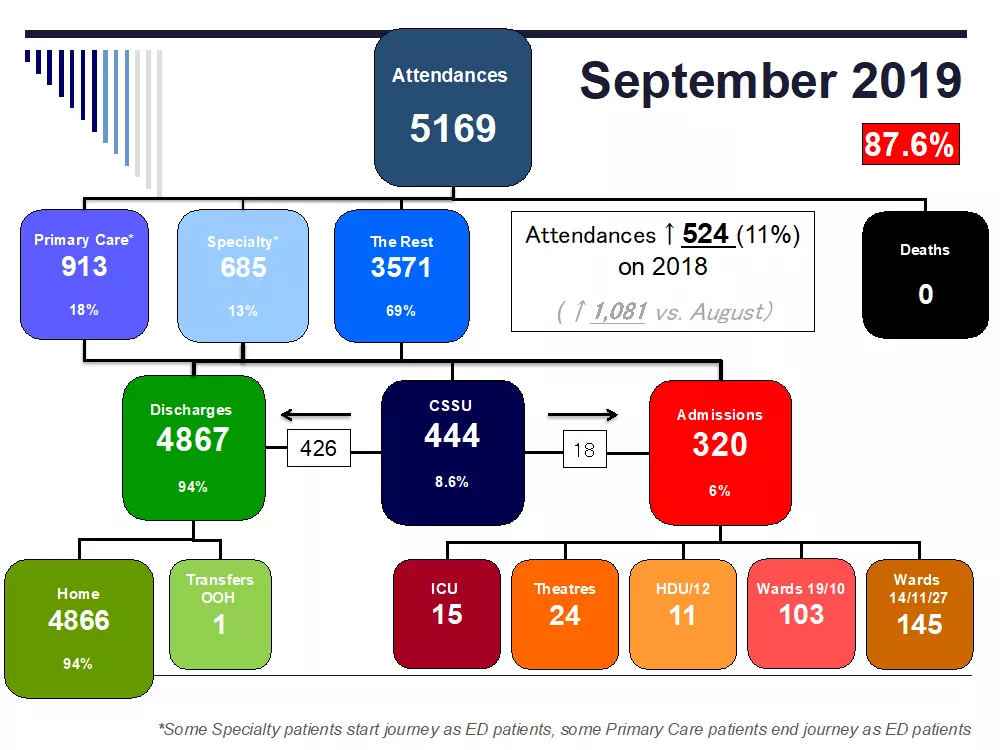

The four-hour target, a measure often used to demonstrate performance, is a complex measure with multiple confounders as to how it is derived and interpreted. Our unit would argue that we have maintained a status quo despite an increase in attendances and flat line staffing, which demonstrates that our approach is having an impact. Furthermore, our admission rate to a ward bed has reduced over time demonstrating we are still able to sift and sort appropriately even in times of high demand. There is some non-significant data on our complaint rate which, if measured per 1,000 patients, is improving over time.

What did it cost to set this up?

The biggest cost items are increasing staffing during surge periods (ie an extra consultant on the late shift); we have now moved to having eight (approximately 5.5-6 whole time equivalent) consultants as a direct result of the need to support winter pressures.

The smaller, intangible costs are senior team time in meeting and developing escalation plans, plus time spent maintaining morale during the winter period.

A longer term strategy that has clearly brought benefit for the department has been the creation of a “single front door” in Leicester. This required funding to build a new ED with capacity to host the paediatric acute team and the creation of a co-located Children’s Short Stay Unit (CSSU). This clearly required significant capital investment but has enabled us to provide a comprehensive acute paediatric service with both ED, Paediatric ED and paediatric staff working alongside each other. The benefits of this co-working have yet to be fully realised in relation to teamwork and education, but are considerable. Furthermore, the patient experience is considerably improved in relation to the sometimes unnecessary double clerking that occurs as a patient moves through the system.

What advice can you share?

Senior staff must role model positivity. This is not being falsely optimistic, but a consultant who looks deflated and brow-beaten will definitely spread this emotion like a contagion.

Dr David Sinton set up the Greatix programme (see Figure 3 below) which allows staff to feed back to others on interventions that have been helpful, morale bosting or worth sharing. This learning can then be noted and implemented if required.

Dr Gareth Lewis facilitates our CRITICally CAREful Forum in which we review data from the previous month and share learning from sentinel cases. This has been highly influential at flattening hierarchy in the department as cases are presented non-judgmentally and demonstrate the errors that all staff are prone to making regardless of seniority.

However, probably most important are specific behaviours by senior staff: listening, taking about positive things that have happened on shift, delivering feedback sensitively an appropriately. All of these will have an impact on staff wellbeing.

For further information please contact: Rachel.rowlands@uhl-tr.nhs.uk

Disclaimer: RCPCH have been notified that the above is a good example in managing winter pressures in emergency departments and will be reviewed on a regular basis. Sharing examples does not equate to formal RCPCH endorsement.