What was the challenge?

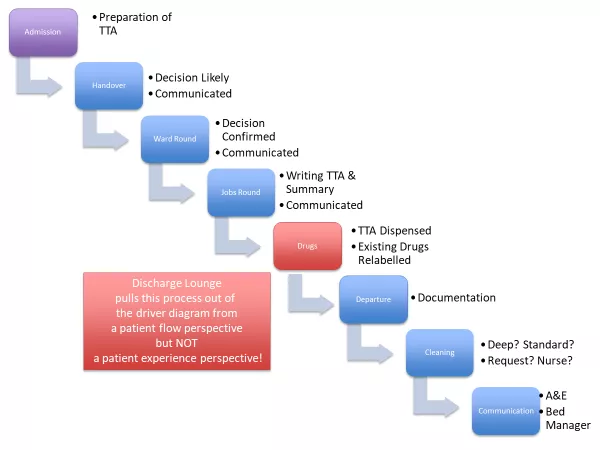

Any pinch points in the patient-flow pathway can cause significant delays in winter. The decision to discharge a patient may be taken as early as the morning handover meeting at 08:30. Yet in winter months, bed spaces were often not freed up until the afternoon or evening.

A ‘discharge lounge’ was already intermittently available, dependent on staffing levels. A ‘discharge culture’ of pre-emptive discharge summaries and TTA (to take away) -writing was encouraged. Patient transport times and cubicle cleaning times were somewhat out of our hands.

The most significant delay in the patient-flow pathway was the time taken for patients to receive their discharge medications (see Figure 1 below). As part of a major tertiary trauma centre, with 845 beds, joining the inpatient pharmacy queue was providing significant delays of around four hours post decision to discharge.

The demands placed on pharmacists are not as simple as needing new short-term medication, which can be dispensed from a TTA (to take away) cupboard on the ward. Existing medications often needed relabelling (for example, if a valproate dose is increased, you cannot just discharge the patient with verbal instructions – the bottle must be re-labelled).

What did you do?

A satellite dispensary was set up on discharge lounge with a label printer and drugs cupboard, specific to paediatrics.

A dispensing pharmacy technician was employed for half a day per week to staff it. He or she would process TTAs and also re-label admission medications with new doses, as prompted by the pharmacy ward rounds.

What impact did this have?

The previous mean average wait for medications had been recorded by inpatient pharmacy as four hours. This was measured from the point of receipt of a prescription up to the medications being ready for collection. It therefore did not include additional delays such as portering.

After the instigation of the new pharmacy, the maximum wait for a TTA prescription to be processed dropped to 20 minutes. This included delivery of the drugs to the patient.

The knock-on effect was a significant reduction in delays and breeches in A&E for reasons of ‘waiting for bedspace to be available’.

What did it cost to set this up?

The costs for the drugs cupboard and label printer were one-off expenses, which were for infrastructure able to stay in place all year round. This investment means that in future winters the same reduction in flow time can be achieved at a reduced cost, simply with the employment of a pharmacist half a day per week.

This year we will be looking at whether pharmacy staffing can be expanded further, especially at weekends.

What advice can you share?

Many DGHs will be too small to set up a paediatrics-specific satellite pharmacy. But it would be possible to ‘team up’ with other departments or directorates and share such a resource.

For further information please contact: keir.shiels@nhs.net

Disclaimer: RCPCH have been notified that the above is a good example in managing winter pressures in emergency departments and will be reviewed on a regular basis. Sharing examples does not equate to formal RCPCH endorsement.