Child health during the war

The war affected the health of all the population, especially children. Common health problems included head lice, skin diseases and poor nutrition caused by rationing of food, clothing, soap and footwear. But the mental health of young people also suffered.

Ten percent of the country’s population was evacuated and most were children. They needed support to deal with the effects of separation and loss of homes and family members. And there was a general lack of childhood: there were no new toys or clothes, and children helped out with the war effort from collecting salvage and running errands to helping with farming.

The war was a key time for the RCPCH (formerly the British Paediatric Association or BPA). It grew from a friendly club to an organisation that actively sought to influence policy and support health professionals during and after the war.

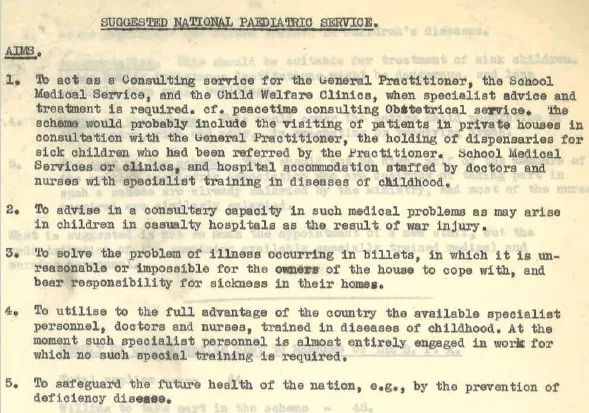

National Paediatric Service

The war took place before the foundation of the NHS in 1948, and so was a time the BPA advised on how health services could cope with the new challenges. One proposal was for a National Paediatric Service with the aims of:

- maintaining child health and caring for the sick child

- assigning paediatricians to different zones of the country in order to make sure there was specialised care everywhere

- utilising GPs (general practitioners), nurses and other medical officers

- training all health practitioners in basic paediatrics.

The BPA believed the service would be a good way to ensure resources were adequately spread across the whole of the UK, making it more likely the health of all children would be looked after.

However, the service did not deal directly with the casualties of war, and the proposal was unsuccessful. One argument against the scheme was that “the British people have a capacity for making things work and I am not altogether satisfied that, muddled are the present facilities, the results are not as good as they would be under any other scheme.”

Nutrition

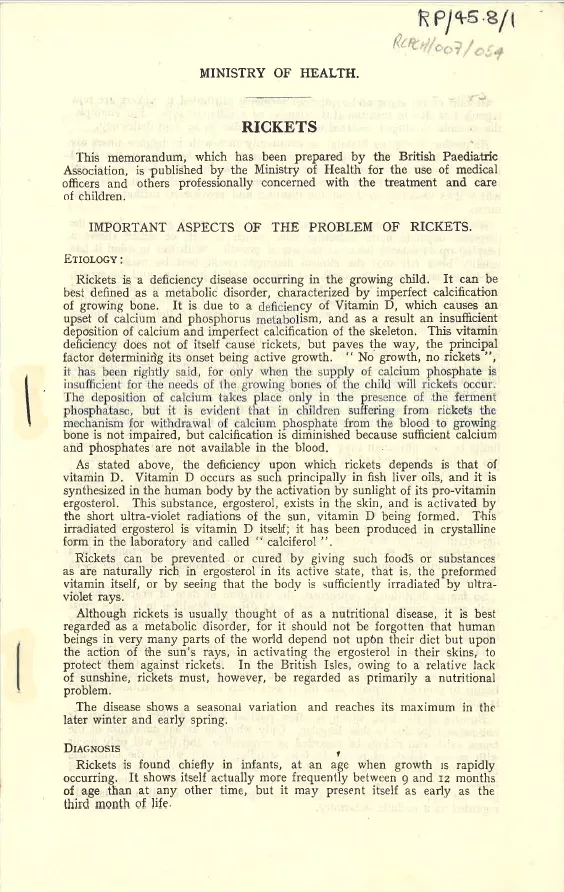

A major challenge was preventing ill health caused by poor nutrition. Throughout the war, there were shortages of certain food, and rationing was introduced to make sure everyone got a fair share. Each person (children included) had a ration book with coupons used to purchase rationed goods, and all food had a fixed price at every shop to prevent people being unable to afford certain things in their local area. There was still a short supply so sometimes when rations were low, people could wait in long queues only to discover what they were waiting for was sold out.

Rationing was in place until 1954. And, some items that weren’t rationed during the war were later rationed, such as bread, which was readily available during the war and rationed in 1946, a year after the war ended. Since rationing was in place for so long and food from overseas was especially difficult to get, some children grew up without seeing a banana. It wasn’t just food that was rationed - clothes, petrol, paper and soap were also in short supply.

There was a surplus of some foods, though. Carrots were easy to grow in gardens, which led to carrot jam, carrot curry, carrot lollies (a raw carrot on a stick) and carrot pudding. In 1942, the Ministry of Food created Dr Carrot to encourage children to eat more.

During wartime rationing, it was important that everyone got the right nutrition to stay healthy and grow. Children got more eggs and milk and were encouraged to eat more fruit, vegetables and fish. But health issues caused by poor nutrition, such as rickets, still increased. During the war, the BPA carried out research into the quality of milk as well as the rise in rickets, and circulated diagnosis and treatment guidance.

Evacuation

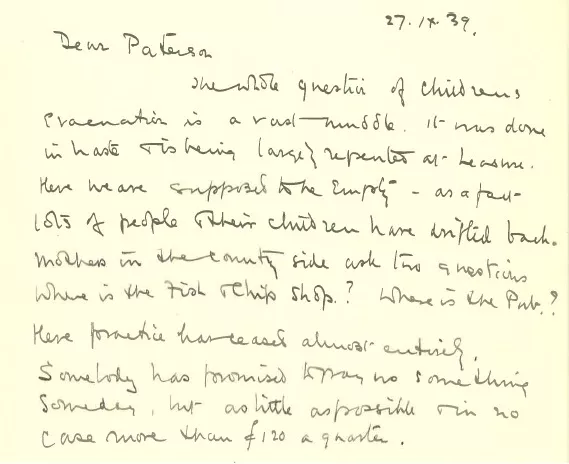

This was the biggest cause of disruption to children’s lives as children in Britain were sent to places of safety in fear of bombing. The scheme was voluntary, but many families took part, especially when schools closed and offered transportation to the countryside.

Evacuation happened in phases. The first was two days after the start of the war, but almost half of these children had returned home within three months when expected bombing had not taken place - and the second when the Blitz began in September 1940.

As the child population shifted across the country, there were new challenges for health services, as smaller local hospitals became overcrowded and doctors taking part in the Emergency Medical Service were placed in new locations to help with influxes. At the start of the war, there was uncertainty about payment and how long doctors would spend in places.

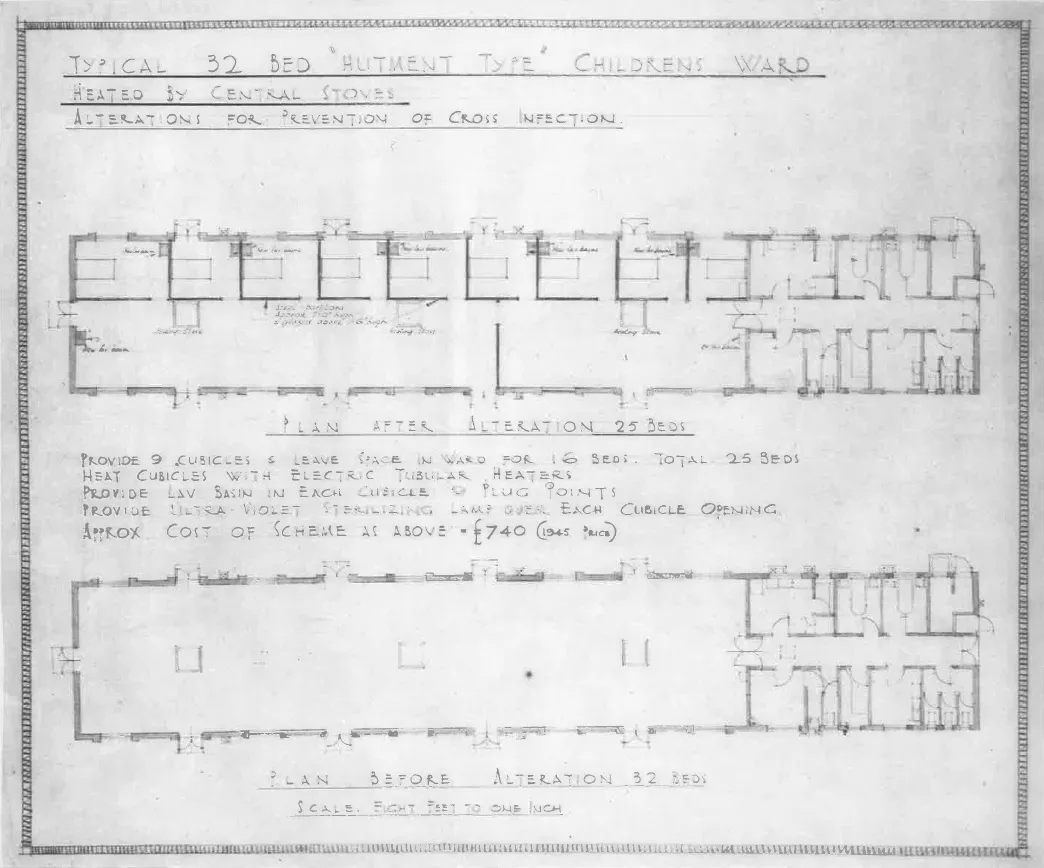

The BPA realised overcrowded hospitals and the design of the wards was resulting in cross-infection on children’s wards so introduced new designs to cope with the numbers of patients while maintaining good health as much as possible. The BPA also advised on post-war planning for paediatric services across the country, something very similar to our invited reviews process today.

After the war

During World War II the BPA worked alongside other organisations and individuals to safeguard the health of children suffering from the effects of war, to by influencing policy and supporting doctors and health professionals.

But when the war ended in 1945, the work didn't stop. The effects continued to impact physical and mental health. The welfare of the people was a main priority of the government and the NHS was formed at a time of innovation spurred on by the war. This included building or restoring hospitals, better medicines and new medical technology based on wartime electronics.

After the war, BPA grew as an organisation, eventually becoming a Royal College in 1996. But over 80 years, our core aims remain the same: to advocate for better child health whether in war or peace.