1. Background

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) is committed to protecting personal data from unlawful disclosure, in accordance with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018. This commitment extends to all RCPCH activities and outputs, particularly those involving the collection, processing, and reporting of survey-based data and patient-level data.

The National Clinical Audits at RCPCH, in particular, are authorised to collect and process specified confidential patient information without consent, with approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) under section 251 of the NHS Act 2006, and equivalent ethical approvals/common law duty of confidentiality for devolved nations and crown dependencies. These audits are commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) to report comparative statistics on the quality of care and outcomes for infants, children, and young people across the UK. The aim is to stimulate quality improvement and help organizations ensure that healthcare aligns with national guidelines and standards.

This guidance provides a framework to achieve the right balance between minimizing the risk of disclosure and maximizing the public utility of the data through a bespoke assessment of the data and its presentation. It replaces the RCPCH 'Small Numbers Policy,' which advised a blanket suppression of any result linked to fewer than five individuals.

The guidance is based on the Office for National Statistics (ONS) policy on protecting confidentiality in tables of birth and death statistics, along with the Government Statistical Service's disclosure control guidance for tables produced from surveys.

2. Aims and scope

The aim of this document is to provide RCPCH staff with the guidance they need to reduce the risk of unlawful disclosure of personal information, while maximising the usefulness of data. It applies to all statistical outputs, whether in a scheduled publication, or in any correspondence generated by staff in response to an ad hoc query.

A secondary aim is to inform the general public about the methods used by the College staff to protect their confidentiality and that of their families in the context of data outputs.

This guidance focuses on the risk assessment of aggregated outputs, and the disclosure control methods to be applied at the point of publication and sharing. It does not specifically cover the measures in place to protect individual records throughout the data's lifecycle, such as pseudonymisation and data storage. All data collected and processed by the RCPCH Audits Team is held on secure servers which comply with all Data Protection Legislation requirements and are hosted within the UK.

For more information, please visit the Data Protection and Confidentiality policy at the RCPCH.

This Policy does not cover any of the following disclosure requests:

- a request made by a Regulatory body

- a request/order made by a court or coroner

- a request made by an Authority, such as the Police.

If RCPCH is not the data controller of the personal data being requested, these requests must be immediately forwarded to the data controller and RCPCH Information Governance informed.

If RCPCH is the data controller of the personal data being collected, the College’s Third Party Disclosure Procedure will be followed.

This guidance also does not cover individual rights requests. For further guidance see Appendix A of the RCPCH Data Protection Policy.

3. Main concepts

Even when data appears anonymised, there is still a possibility that individuals could be identified and sensitive information inferred. This section outlines what constitutes unlawful disclosure, explains what types of information are considered protected, and introduces key concepts and techniques used to minimise disclosure risk.

Unlawful disclosure may occur when an output contains sufficient detail that a motivated reader can use to identify an individual and find out protected information about them. Identification might be based on the published information alone, or combined with some other information.

There is not usually an unlawful disclosure when:

- a person can be identified but nothing new can be learned about them (simple recognition)

- a person can identify themselves, but others cannot identify them (self-recognition)

- a person believes they can be identified or can recognise someone else, but there is no certainty that this is the case.

- Protected information

-

Protected information is information which, if it can be related to an identified individual, reveals a fact about them or someone else that is confidential, or is likely to cause damage or distress to someone.

- Disclosure control

-

Disclosure control refers to a set of techniques for reducing the amount of detailed information in a statistical output to prevent an unlawful disclosure, or at least reduce the risk to a very low level. It is unreasonable to aim for the complete elimination of the risk of disclosure.

- Types of disclosure risk

-

These are various ways in which seemingly anonymised data can still pose threats to individual privacy. The main types of disclosure risk include:

- Identity disclosure: When an individual's identity can be directly inferred from released data, compromising their privacy.

- Attribute disclosure: When sensitive attributes or characteristics of individuals can be determined from the data.

- Group attribute disclosure: When sensitive attributes of a group can be determined from the data. It can occur when all respondents fall into a subset of categories for a particular variable.

- Inference/deductive disclosure: When sensitive information can be deduced either by combining information within the same publication, or with external information or background knowledge. The main types of deductive disclosure include:

- Disclosure by differencing: Involves a motivated reader using subtraction within the same table, or two or more overlapping tables, to gather additional information.

- Spatio-temporal disclosure: When a combination of spatial and temporal information can lead to the identification of individuals or their sensitive information. Overlapping geographical areas and rolling multi-year aggregates can also potentially lead to disclosure through differencing.

- Linkage disclosure: When seemingly anonymous data points from different sources can be linked to the same individual. These sources can include other statistical outputs that have been published or supplied on an ad hoc basis to the same data customer, and publicly available information such as government datasets, news, reports, and social media platforms.

- Contextual disclosure: When contextual details provided alongside the data allow readers to identify or infer sensitive information about individuals.

- Disclosure by reverse engineering: When the mathematical formulas used to obtain some statistics on a small group of individuals, can be reversed to get the original data. For example, if the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum are given for a small group of children.

4. Main principles

This section outlines the safeguards in place for handling personal identifiers and individual-level datasets within the RCPCH, as well as the principles and considerations that guide the disclosure risk assessment.

- The protection of personal identifiers

-

All personal data that can be used for the direct identification of an individual (e.g. NHS number, date of birth, postcode) will be pseudonymised, and the corresponding key will be securely stored separately.

- The protection of individual level information and datasets

-

Patient and episode level datasets containing various connected pieces of information about individuals, will only be shared with the unit/ hospital/ Health Board or Trust that initially submitted the data. In the case of the national audits delivered by the RCPCH as part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP), information may also be shared with those that have received approval from the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) via their Data Access Request Service, the NHS Scotland Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care (HSC-PBPP) or equivalent bodies in other devolved nations and crown dependencies. This approval is contingent upon the applicant demonstrating appropriate intent for use of the data, and proper information governance. If identifiable data is to be transferred, the applicant must have their own Section 251 approval in place, or equivalent authorization in devolved nations or crown dependencies.

Patient and episode level datasets are stored, processed, communicated and transferred securely, in accordance with RCPCH information security standards. For further information on these please contact the Information Governance Team.

All members of staff with access to protected information must have appropriate data protection training. Including the E-learning module about GDPR and confidentiality designed and hosted by the Medical Research Council Regulatory Support Centre.

- The concept of 'protected information' at the centre of the risk assessment

-

The concept of protected information is key in the risk assessment. The following questions may guide the analysis:

- Can any individual be identified from the table, graph, or text, with any reasonably high degree of certainty?

- If so, is any new information revealed about them?

- Is any information revealed about any other living person connected with them, with a reasonably high degree of certainty?

- Is this new information likely to cause damage or distress?

Small numbers, even unique cases, are not necessarily disclosive. For example, according to the ONS, a table may indicate that a person was born in a specific area and time period, but the mere fact of birth does not in itself disclose any new information about the individual or their family. Hence, it does not require disclosure control in the absence of other data dimensions.1

The evaluation of possible damage or distress is also important. The ONS states: “the relatively common possibility that a table might reveal or confirm a potentially identifiable individual’s sex or their age in years is considered too trivial to require protection for its own sake, bearing in mind the need to balance confidentiality against the utility of the statistics”.1

- Self-identification

-

Each individual possesses a unique set of information about themselves that facilitates self-identification, and this, in itself, does not constitute unlawful disclosure. Disclosure may occur when individuals, by identifying themselves, are also able to deduce information about others, or when individuals discover something unexpected about themselves, such as a unique or rare attribute.

- Uniqueness or rarity

-

Uniqueness or rarity is one thing to look for when thinking about whether disclosure control might be necessary. It may encourage others, such as researchers or journalists, to seek out the individual or their relatives. The threat or reality of such a situation could cause harm or distress to the individual.

- Combining information

-

The main principle behind each disclosure process is to ensure that any output contains information that could be used either on its own or in conjunction with other data to deduce protected information. The analyst will consider the different types of disclosure risk, especially:

- If it is possible to deduce information through comparison. This includes using totals by rows and columns within the same table and combining separate tables within the same report.

- If it is possible to do so against previous publications.

- If it is possible to link the information to other publications available online.

5. Balancing utility and risk

When applying statistical disclosure control the aim is to balance utility and risk. The published outputs should assist the user as much as possible in their need for statistics without disclosing protected information.

The core users of the Clinical Audits at the RCPCH include:

- national bodies, who are interested in overall trends that can guide the development of policies, standards, and programmes

- regional networks and other intermediate organisations, seeking to bridge the gap between clinics/hospitals and improve healthcare provision

- unit level users (hospitals/Health Boards or Trusts), looking to compare their own results with other units and identify areas for improvement

- parents/carers and patients, who may have an interest in national trends and wish to compare their unit or hospital against others.

RCPCH data processing activities such as its national audits may collect, process, and publish information regarding socio-demographic characteristics, completion of health checks and care processes, health outcomes, medical treatments, and the use of technologies. By nature, some of these categories are more likely to contain protected information than others. However, the application of disclosure control will depend on the circumstances.

Below are some points for consideration when balancing utility and risk for each category of data collected in the clinical audits. The disclosure risk of each variable and category is analysed, assuming the absence of other data dimensions that could potentially lead to the disclosure of protected information.

- Age

-

- Utility: A detailed description of the number of children by age can help understand the incidence of the medical conditions examined by the audits, and aid in strategic planning.

- Risk: The disclosure of the age of a child is not likely to cause damage or distress, if it can’t be linked to other sources of protected information.

- Special consideration: Disclosure control may be applied if the incidence of the condition is very low or rare for certain age groups (e.g. there is only one child younger than 5 years old with Type 2 diabetes in England and Wales).

- Sex

-

- Utility: The incidence of medical conditions and the effects of certain medical treatments often vary depending on the biological sex of the individual. A detailed breakdown of the number of children by sex can help us better understand, raise awareness about, and inform decision-making regarding these differences.

- Risk: Given the differences between biological sex and gender, and considering the expectations of each individual to be recognised by their chosen gender, disclosure control is suggested for the variable 'sex'.

- Special consideration: When the variable 'sex' refers to very young children, the risk of disclosing new information likely to cause damage or distress decreases. However, it's important to consider that this information may remain in the public domain for many years.

- Ethnicity

-

- Utility: Having a detailed breakdown of the number of children by ethnic group is crucial for understanding the variations in the incidence of medical conditions and for addressing persistent differences in health outcomes and treatments.

- Risk: The clinical audits collect ethnicity data on the basis of self-declaration. Ethnicity data is often considered a sensitive or personal characteristic that should be protected from disclosure to avoid discrimination. The more detailed and specific the information about ethnicity (e.g. White Irish vs White), the higher the risk of disclosing protected information.

- Deprivation

-

- Utility: A detailed description of the number of children by deprivation is key to understand the persistent variation in health outcomes and access to treatments.

- Risk: The level of deprivation is derived from the local super output area (LSOA) in which children and young people reside. There is a low risk of identifying a person based solely on the level of deprivation, particularly when it is presented in aggregated groups (e.g. deprivation quintiles). However, self-identification and being identified as the only member of a group living in an area of high deprivation could potentially cause distress and fears of discrimination.

- Care processes

-

- Utility: A detailed description of the number of children receiving each recommended care process, facilitates the monitoring of compliance levels in units, regions, and nationwide. This information aids in identifying areas that may require additional support.

- Risk: The fact that a clinical activity took place is not considered protected information.

- Special consideration: should be given to selective care processes that are only performed under the suspicion (or as a result) of an underlying condition, as this may disclose the physical or mental well-being of individuals (e.g. a child being recommended for additional psychological support).

- Health outcomes

-

- Utility: The monitoring of health outcomes is a key reference in the development of standards and policies. At unit and regional level, it helps identify areas of improvement.

- Risk: In principle, all health outcomes should be subject to disclosure control, as they describe the physical or mental well-being of individuals.

- Special consideration: There are at least two situations where the utility of disclosing outcomes may surpass the risk.

- First, when the outcome is positive. For example, there are only two children in a paediatric diabetes unit, and both have a median HbA1c below 58 mmol/mol. Putting this information in the public domain can help with benchmarking and decision-making while carrying a low risk of causing harm or distress to the individuals.

- Second, when there is a low risk for the individual to be identified and targeted. For example, a report shows that in 2022, 1.6% (2/122) of babies being cared for in Special Care Units (SCUs) in the UK experienced necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). This data provides valuable information about the low incidence of NEC in SCUs and carries a relatively low risk of identification. However, ensuring the absence of other online datasets about NICU babies' care, which could potentially lead to their identification, is crucial.

- Medical treatments and the use of technologies

-

- Utility: Publishing data on the use and outcomes of medical treatments and technologies enables healthcare professionals to benchmark the effectiveness of different methods, enables the identification of gaps, and facilitates well-informed decisions regarding resource allocation.

- Risk: This information may reveal details about an individual's health condition. It can also be used to target individuals for studies on the effects of specific treatments or technologies. Disclosure control is highly recommended.

6. Strategies for disclosure control

A number of techniques can be applied to protect outputs. These all reduce the utility of the statistics in some way, but some are more perturbative than others.

It is important to consider that graphs and figures can be as disclosing as tables and text, particularly when presenting patient-level information in scatterplots, histograms, boxplots, and maps. The data used to create graphs and figures should be subjected to the same disclosure control techniques as the data presented in tables. Additionally, there are specific techniques that can be applied to graphics.

Common disclosure control techniques include:

- Aggregation

-

Aggregation. Combining data into broader categories or ranges to reduce granularity. This technique is considered non-perturbative as it doesn’t change the original figures.

- Rounding

-

Rounding rates and percentages to a lesser level of precision to avoid the deduction of very small numbers. Non-perturbative.

- Suppression

-

Suppression. Withholding specific values or categories from the data to prevent direct identification.

Example:

- Suppression of all figures below a particular threshold (i.e. small numbers suppression).

- Secondary suppression

-

Secondary suppression. Withholding specific values to avoid the deduction of small numbers.

Examples:

- Reporting that 99/100 children had a good outcome is just as informative as reporting that 1/100 children had a bad outcome. High numerators, that approach the denominator, are as informative as small numbers.

- When only one category or cell in a table meets the criteria for small number suppression, and the totals are known, another category should also be masked (or combined) to prevent disclosure through differencing.

- Smoothing

-

Smoothing involves applying a mathematical function to the original data to create a smoothed (less variable) representation of the underlying trends.

Example:

- Representing the moving average (i.e. the average of two or more periods of time) instead of the real figures for each period in a time series.

- Binning

-

Binning involves grouping data points into discrete intervals or bins.

Example:

- Most statistical and visualisation software applications allow the user to predefine ranges or bins when creating a histogram.

- Heat maps and colour gradients

-

Heat maps and colour gradients can represent data values, allowing for comparison while minimising the risk of disclosure.

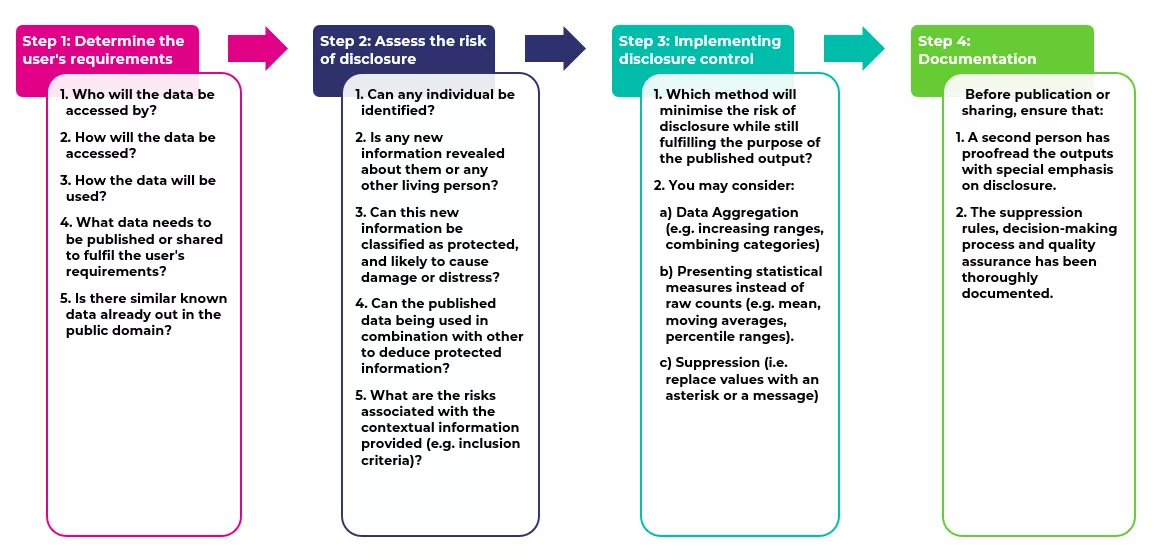

7. Summary of steps for assessing and mitigating data disclosure risk

You can download this diagram below.

- Step 1 – Determine the user's requirements

-

- The requirements for the processing of national audit data, as does also to other data processing activities undertaken across the College, is set out on the related team specific RCPCH web pages. In the case of the RCPCH national audits this includes details of the purpose of the data collection, its intended use and details of the audit analysis methodologies.

- The data collection allows those working within the healthcare systems to have access to accurate and up-to-date information in a timely way. This may include access to identifiable data that is protected through robust approval, encryption and access control processes.

- Audit outputs are published to provide the public and health services with insights into the current state of the quality of care.

- In the case of HQIP-commissioned national audits delivered by the RCPCH, ad-hoc data can be requested via an application to the HQIP Data Access Request Group (DARG) using their Data Access Request Form (DARF), where the requestor is required to specify the purpose of the project, provide a detailed description of the information fields, the level of granularity and time period, and offer a summary of any relevant submission history. Each request is carefully reviewed and approved by the HQIP DARG, as the commissioner and data controller of the national audits within the NCAPOP.

- Step 2 – Assessing the risk of disclosure

-

Audit data, in particular, has inherent characteristics that increase the risk of identification, first, because it is specific to a particular group of children who are associated with a medical condition that is the subject of the audit, and second, because it is both time-sensitive and geographical in nature. Potentially, any number referring to fewer than three individuals in a table or graph could lead to identification. However, as explained in this guidance, the identification of individuals does not necessarily imply the disclosure of protected information about them.

When assessing the risk of disclosure, the audit analyst will consider:- a. The sensitive nature of the data, as described in section 4.

- b. The possibility of this data being used in combination with other data to deduce protected information. Different types of deductive disclosure risk were described in section 3.

- c. The risks associated with the granularity of the data, whether it is by geographical, institutional or demographic groups, as well as the contextual information provided (e.g. the inclusion criteria, and the definition of numerators and denominators).

- Step 3 – Implementing disclosure control

-

After the risk has been identified, it should be weighed against the utility of the data before the potential implementation of disclosure control, as outlined in section 5.

If disclosure control is applicable, the selection of the method will depend on the type of data and the purpose of the published output, as outlined in section 6.

General best practices to prevent disclosure include:- Setting a minimum threshold for the publication of data that could lead to the disclosure of protected information. If the number of cases or data points falls below the threshold, consider suppressing or aggregating the data to a higher level.

- Generalising data by combining categories or ranges whenever possible.

- Displaying percentages or ratios instead of raw counts.

- Presenting data in aggregated forms using statistical measures such as the mean, median, moving averages and percentile ranges.

- Rounding aggregated numbers to a reasonable precision (e.g. avoiding the presentation of decimal points when publishing percentages).

- Utilising visualisations that represent data trends without exposing exact values (e.g. heatmaps, smoothed trend lines, IQR lines).

- Step 4 - Documentation

-

After adhering to the previous steps and prior to publication, teams publishing data will ensure:

- A second person who hasn't authored the document will perform a proofread with a special emphasis on ensuring there is no disclosure of protected information.

- The suppression rules, decision-making process and quality assurance has been thoroughly documented.

Always aim to publish as much information as is feasible. If there are compelling reasons not to make specific figures publicly available, explore alternative ways to share the data with the relevant stakeholders.

An audit trail of data releases and ad-hoc requests should be kept, in order to minimise the risk of disclosure by differentiation against previous publications. The trail of ad-hoc requests should include the name and contact details of the individual or organisation requesting the data, the requester’s explanation of “public good’ purpose, the data specification and any legal details relevant to the data release.

8. Examples

You can download examples of managing data disclosure risks in public reports and dashboards below.

- 1a1bStatistics, Office for National. [Online] https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/methodologytopicsandstatisticalconce…